I’m publishing this blog on Sunday 6 September, which is fathers’ day in Australia and New Zealand, but hardly anywhere else (e.g. it’s June in the US, UK, Canada, China, etc). Well, turns out there are several fathers’ days, which is fair, because there are several different kinds of father.

The father in this movie is a keen family man, and also a cannibal. The patriarchal symbolic order of this family is: the father catches them, the mother (or daughter) slaughters and cooks them.

If the prey weren’t human, some might consider that “normal”.

This time last year (on father’s day down under) I blogged about a Mexican film translated to the same as this one: We Are What We Are (Somos lo que hay). Now, we all know that American remakes of “foreign” (i.e. non-American) films can be disastrous (remember Godzilla?) and, to be fair, Jim Mickle, the director, did not like the idea of remaking the excellent Mexican version just so American audiences did not have to read subtitles. But he and co-screenwriter Nick Damici came up with a new angle. In the Mexican film, the father dies, causing family conflict over the role of cannibal patriarch; in this one, it’s the mother that dies, and the children must decide whether to follow the tradition and authority of their father, or follow their own paths.

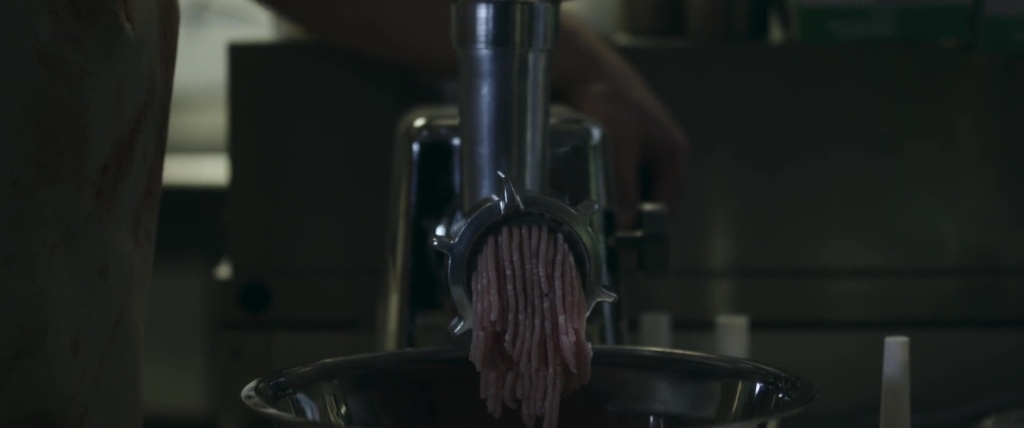

Frank Parker (Bill Sage) is left widowed when his wife starts shaking and bleeding from the mouth, then collapses, falls into a ditch and drowns. She has just finished shopping at the general store where, through the pouring rain, a butcher carries a dead pig from a truck marked “Fleischman’s” (German for meat man) – the pig’s corpse is cut up and the flesh is minced.

What they’re doing to the pig would usually be considered unremarkable, except that, knowing this is a cannibal movie, we expect the same thing will happen to humans somewhere around the end of Act I.

This is an ultra-religious, white family in the rainy Catskills, and everything they do is avowed to be God’s idea. The daughters, Iris (Ambyr Childers) and Rose (Julia Garner from Ozark) explain to their little brother that he can’t have his cereal, because the family is fasting.

Fasting is usually followed by a ceremonial feast, which this family calls “Lamb Day”.

It is a family tradition passed down from 1781 – we get a flashback via a family journal which is handed to Iris – it was started by their ancestor Alyce Parker (Odeya Rush from Goosebumps) when her father fed them their uncle in one of those pioneering cannibalism events with which American history is so replete (think the Jamestown “starving time” several decades earlier, or the Donner Party several decades later). The Parker descendants have been cannibals ever since.

Their religious tradition requires eating human flesh on special occasions; while the wider community’s ritual anthropocentric carnivorous sacrifice requires the (far more regular) consumption of other mammals, such as the pig being carried through the store.

Eating meat requires the “deanimalisation” of the chosen victim, often by dividing the carcass up into named components like “spare ribs” or “rump”. The Parkers work the same way. Like a cooking show, we witness them “process” the carcass, then cook and consume the flesh; only worth filming because we know (or willingly suspend our disbelief) that this is human meat.

Rene Girard says we maintain social amity by the sacrifice of a surrogate victim, a symbolic consumption of our violent impulses – we eat an outsider instead of warring with each other. For most people, it’s a non-human animal; for the Parkers, it’s whoever is unlucky enough to get a flat tyre near their property. In stark contrast, the Parker’s neighbour Marge (Kelly McGillis from Witness) is vegetarian, and her offers of help to the family are variously accepted or brutally rebuffed, depending on whether it’s Lamb Day. Marge gets a hint that cannibalism, extreme carnivorism, runs in the family when she steps in to nurse the sick little brother. Has he inherited the family hunger?

Cannibalism movies often cling to the Wendigo hypothesis – that there is a metaphysical force that drives the eaters, once having tried human flesh, to crave ever increasing amounts of it – to need it for their very survival. A classic of this genre is Antonia Bird’s film Ravenous. In the original Mexican version of this film, the family believe they need their cannibal ceremony to survive. It’s the same in this version, with the father convinced that when he gets shaky and his mouth bleeds, this means God is telling him it’s time for Lamb Day.

But there’s a modern twist. The town’s (apparently only) doctor (Michael Parks) performs an autopsy on the mother, which reveals that her ailments were more closely related to the disease kuru, which killed hundreds of Fore people in Papua New Guinea and was believed to have been caused by eating the brains and spinal columns of dead relatives in funerary rites.

Then the doc’s dog finds a human bone washed downstream by the floods, and he begins to suspect what happened to his own missing daughter.

Kuru is a prion disease, similar to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or “mad cow disease”), and is often quoted as a reason why we shouldn’t eat people, in case they have abnormal prion proteins, although that argument is no more convincing than the one against eating cows in case they have BSE (safest option for avoiding spongiform encephalopathy is: go vegan). At any rate, this family have been engaging in cannibalism for some 240 years, believing they are doing God’s will, and hey, who invented kuru anyway?

As Hannibal would say – “typhoid and swans – it all comes from the same place”.

The father’s day feast at the end of the movie is spectacular, and the girls drive off with the diary from 1781, unaware of the kuru diagnosis, and presumably still believing in the necessity to obey God’s will and eat people occasionally. Honestly, it wouldn’t be the stupidest thing that’s ever been blamed on the deity.

Rotten Tomatoes gave the movie 86% fresh, with most critics liking it, and a couple of them really detesting it. The London Evening Standard asked:

“Who can resist a good cannibal movie?”

Well, my gentle readers, clearly not us. And this is a good one.

A complete listing of Hannibal blogs can be viewed here:

https://thecannibalguy.com/2020/07/08/hannibal-film-and-tv-blogs/

Pingback: Family feeding frenzy: FRIGHTMARE (Pete Walker, 1974) – The Cannibal Guy

Hello! Would you mind if I share your blog with my twitter group? There’s a lot of folks that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Cheers

LikeLike

Pingback: “We’re NOT Maori cannibals”, FRESH MEAT (Danny Mulheron, 2012) – The Cannibal Guy