If you by any chance have watched any of the videos of the influencer Israel dos Santos Assis, better known online as Pinguim (Penguin), you may not have guessed that anything controversial was being shown. The Brazilian, from São Francisco do Conde, a city in the metropolitan area of Salvador in Bahiahad, had been gaining more and more followers on social media over the months before his arrest on July 23 2024, when he was apprehended after being caught desecrating graves in the cemetery of San Francisco the Count, in the Salvador Metropolitan Region, and stealing human bones.

Not just bones. The 22-year-old influencer used human flesh from the corpses to cook his most popular dish: feijoada, a bean stew usually involved simmering beans with beef or pork. Both of which have been reported as tasting very similar to human flesh.

One of Pinguim’s videos, which went viral on social media, explained the secrets of adding meat to beans — and how to get the most out of the final dish.

“Treat and throw it in the beans. But you can’t eat it, no, you just chew it and then throw it away. You don’t swallow it, you just chew it and throw it away, you just taste it, it’s sweet.”

The remains were not only for use in his recipes. After being arrested, Israel led the local police to a mangrove swamp where he had hidden numerous bags of bones. He had been sending these to Salvador, the state capital, to be used in satanic rituals.

The suspect was caught after families of buried people reported that graves had been violated and several bones had been stolen.

Pinguim made a video confession to police which was later released to the media. He reported that he had spent hours at the cemetery to see which graves were the most recent; those with the freshest human flesh. He told police he had fried a piece of a person’s leg and seasoned it with lemon and vinegar before chewing on it.

Local reports say he told police that he stole the body parts to order, in exchange for a payment equivalent to about $US50 from three people who wanted to use the bones as part of a black magic ceremony. He used the money to buy shoes and sandwiches, as well as getting his hair cut.

Surprisingly, Pinguim was released on bail pending an ongoing investigation into charges of desecrating a tomb. His lawyer, Luan Santos, told local media his client suffered from mental health issues and was taking anti-depressants. He added that he would be demanding psychiatric tests to ascertain whether the accused was fully aware of what he was doing.

Pinguim’s social media accounts have been deleted.

Brazil has always been a fascinating area for students of cannibalism. One of the most famous tribes was the Tupinamba, who captured a German soldier and explorer named Hans Staden in the sixteenth century. He claimed to have witnessed their cannibalistic rituals and did very nicely from his subsequent writings, illustrated by the graphic woodcuts of Theodor de Bry. As a result, the Portuguese came to save the ‘savages’ from their sins, and through enslavement, assimilation, extermination and the introduction of Smallpox, managed to wipe them out completely.

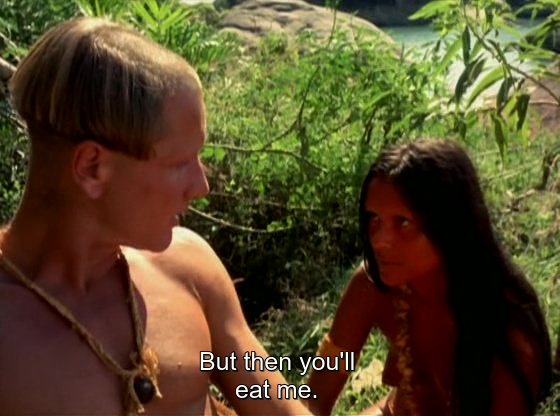

The classic cannibalism film How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês) is set in this period of imperial invasion, and tries to give a new perspective on the way colonialism used cannibalism as its pretext.

More recently, modern Brazilians have been involved in some of the more interesting cannibalism stories that have graced our news cycles, including the “Cartel” who sold pastries made from human flesh to unwitting customers, and the Brazilian who was arrested in Lisbon for eating a man who had tried to help him. Like most cannibalism films, the ones set in Brazil vary between seeing it as something savages naturally do, such as Emanuelle and the Cannibals, and those that see it as typifying the exploitation of the poor by the rich, such as The Cannibal Club.

The Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro proposed a ‘post-structural anthropology’ in his book Cannibal Metaphysics. De Castro sought to ‘decolonise’ anthropology by challenging the increasingly familiar view that it was ‘exoticist and primitivist from birth’, denying that cannibalism even existed, and so transferred the conquered peoples from the cannibalistic villains of the West into mere fictions of colonialism. This alternative view of Amerindian culture rejects the automatic assumption of the repugnance of cannibalism, which serves to either confront it or deny its existence. Accepting those parts of colonial culture that are useful (they speak Portuguese for example) can be seen as a form of reverse, cultural cannibalism.

But Pinguim demonstrates that even Brazilians have not fully embraced this philosophy, particularly when it involves digging up their relatives.

There is a video showing Pinguim confessing to cooking human bodies. More interesting if you speak Portuguese though.