Way back in 2015, when first campaigning for the presidency, Donald Trump announced he would build a wall on the border with Mexico to keep out:

“…people that have lots of problems. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

That seems quite tame now, doesn’t it? Warning about rapists have lost their power, especially given Trump’s own personal legal struggles regarding sexual assault.

So he has turned, dear reader, to our fave subject. Speaking on Right Side Broadcasting Network from Mar-a-Lago, a resort that relies heavily on immigrant labour, he upped the ante on border crossers by calling them cannibals released from mental institutions.

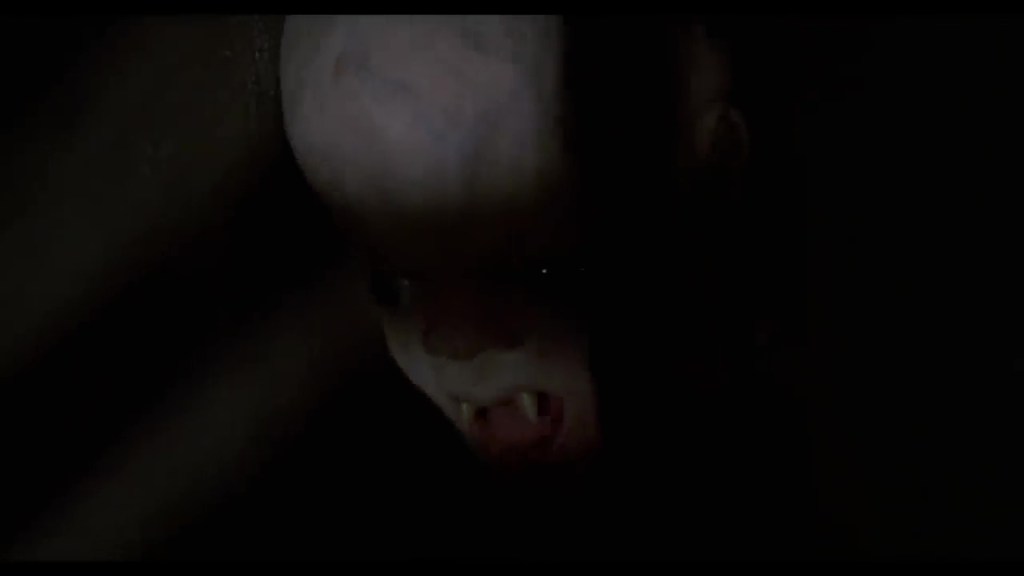

“They’re rough people, in many cases from jails, prisons, from mental institutions, insane asylums. You know insane asylums. That’s ‘Silence of the Lambs’ stuff. Hannibal Lecter, anybody know Hannibal Lecter?”

This is not the first time that Trump has quoted Hannibal. At a rally in Iowa in October 3023, he also spoke of people from insane asylums sneaking into the country, and again quoted Hannibal. He added a rather strange endorsement.

“Hannibal Lecter, how great an actor was he? You know why I like him? Because he said on television on one of the – ‘I love Donald Trump.’ So I love him. I love him. I love him. He said that a long time ago and once he said that he was in my camp, I was in his camp. I don’t care if he was the worst actor, I’d say he was great to me.”

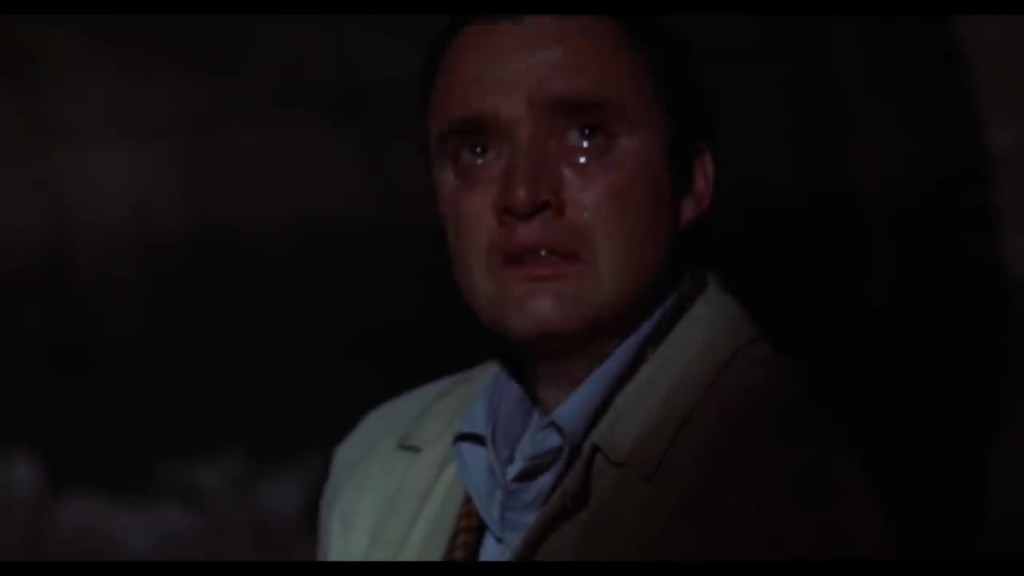

Hannibal Lecter is, of course, not in a position to comment on politics as he is a fictional character born in the mind and the novels of Thomas Harris and born again, we might say, in the films of those books in which Hannibal was played by Brian Cox and then by Anthony Hopkins. Then, in a third coming, Hannibal was rebooted as a Gen-X queer icon in the TV series Hannibal, played by Mads Mikkelsen.

Which of these Hannibals loves, or loved, Donald Trump?

Mads Mikkelsen told CBS News in 2016 that though he could “definitely laugh at some of the stuff [Trump] says, he can also go, ‘Oh my God, did he say that?’ I think he’s a fresh wind for some people.”

Brian Cox called Trump “such a fucking asshole” and “so full of shit.” So Trump is probably not quoting him.

Hopkins, who was born in Wales and became a U.S. citizen in 2000, told The Guardian that he doesn’t care for Trump and explained that he doesn’t vote anyway, because he doesn’t “trust anyone.”

“We’ve never got it right, human beings. We are all a mess, and we’re very early in our evolution.”

Nietzsche wrote of an Übermensch, a super-man who was as superior to ordinary people as they feel themselves to be to pigs. Hannibal clearly sees himself in this role. The mantra of the Übermensch is “Adapt, evolve, become”. But, as Charles Darwin would tell you (if he had not himself become extinct), evolution does not describe a ‘great chain of being’, an evolutionary ladder toward perfection. It is simply about best fitting a niche, surviving a hostile environment while competitors become extinct. The art of evolution is to out-run, out-fight, out-eat the other – to be the last one standing. And the only one eating. Perhaps eating the loser. As Frederick Chilton tells us, “Cannibalism is an act of dominance.”

Early humans seem to have practised cannibalism (according to some palaeontologists), although it may have been more for ritual purposes than for the protein. But in the modern age, protein is king, or at least those who eat the most protein consider themselves therefore superior to nature, and to other humans. Meat is a fetish, an addiction, a way of declaring human, particularly male, supremacy. We confine, torment and slaughter around 80 billion land animals each year (that’s 80,000,000,000) to feed this fetish.

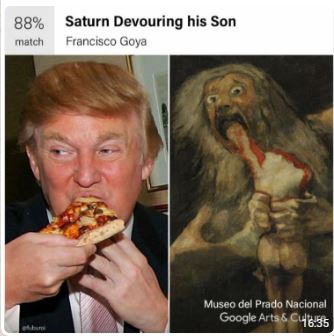

But supremacism does not depend on species – those of another race, another origin, another gender, another age-group may all be dehumanised, objectified like farmed animals, and cannibalism is famously the accusation used to dehumanise colonised people, giving invaders the excuse to enslave or exterminate them. Trump dehumanises immigrants by accusations of cannibalism, just as his political opponents dehumanise him. When American comedian Jon Stewart was asked in 2017 by Late Show host Stephen Colbert to say something nice about then President Donald Trump, he hesitated and eventually blurted, “He’s not a cannibal”. Colbert followed this up a year later suggesting Trump eats human flesh, but only “it’s very well done with some ketchup”.

Consuming the appropriated assets of those considered foreign or inferior is standard operating procedure in human history. In the absence of now largely abandoned concepts of (some) humans being semi-divine creatures, created in the “image of God”, what is to stop the actual consumption of those on the next rung down? As the huge population of humanity consumes the environment, leading to climate change and famine, could cannibalism be the next phase of human evolution?

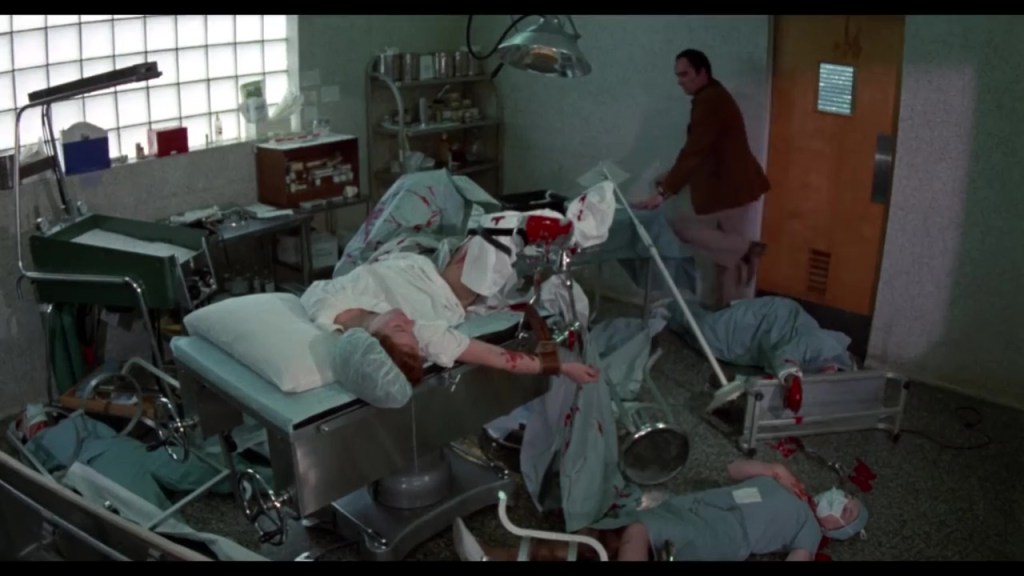

As anthropologist Harold Monroe asks in Cannibal Holocaust, “I wonder who the real cannibals are?”

And as Hannibal said,

“It’s only cannibalism if we’re equals.”