This is an American documentary about serial killers, but specialising in those who ate parts of some of their victims. I guess that makes it inevitable that they will throw the name Hannibal Lecter in there, even though the similarities are not immediately apparent.

There are a lot of documentaries about cannibals, some mostly interested in sensationalism, and others seeking some sort of journalistic accuracy. This is one of the better ones, with a good selection of experts commenting on the various cases.

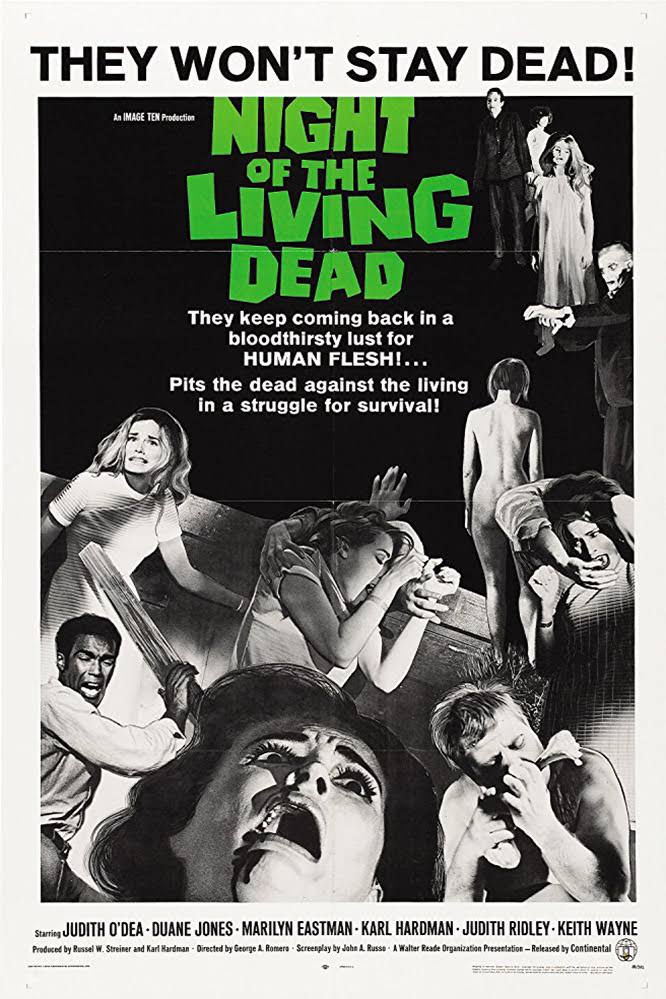

Cannibals, and particularly cannibal serial killers, are a real problem for the media. The difficulty comes from the scepticism that journalists need to cultivate in interpreting a world of stories that are stranger than fiction, or sometimes are fiction disguised as fact, or just fiction that people want to believe. Cannibal books and films fall into the horror genre and are usually lumped together with vampires, zombies, ghouls and other strange monsters out of their creators’ nightmares. So cannibals are a problem.

Cannibals are real. Many cannibals have had their activities thoroughly documented, some are even willing to be interviewed. Jeffrey Dahmer gave a range of interviews in which he spoke openly of the way he lured young men and boys to his apartment in Milwaukee and drugged them, then drilled holes into their heads and injected acid, hoping to create compliant zombie lovers, or else strangled and ate them. Dahmer was killed by a fellow prisoner after serving only a tiny fraction of his sentence of 937 years imprisonment.

But others are still alive – Armin Meiwes is in prison in Germany for eating a willing victim whom he met on the Internet and has willingly given interviews revealing his deepest passions, and he even gets out on day release from time to time. Another documentary reviewed on this site a couple of years ago compared him to, yep, Hannibal Lecter.

Issei Sagawa was arrested in Paris for killing a Sorbonne classmate whose body he lusted after and then eating parts of her, but was not sent to prison as he was declared insane. When the asylum sent him back to Japan, he was released (the French didn’t send any evidence with him), and lives in Tokyo where he has made porn movies, written for cooking magazines, and yes, done interviews for unnerved journalists. There are at least three documentaries on him, which we will get to – eventually.

Documentaries like this one love to compare real-life cannibals, or the much wider field of serial killers, with the fictional character, Hannibal Lecter, “Hannibal the Cannibal”. The problem here is that the serial killers in this doco (or any that weren’t) are not very much like Hannibal. Actual modern cannibals are usually categorised as banal, normal-looking folks who under the polite surface are depraved psychopaths, while Hannibal is civilised, educated, rational, brilliant and independently wealthy. He is a highly respected psychiatrist (until his arrest) and remains a likeable protagonist to many readers and viewers, despite his penchant for murder and guiltless consumption of human flesh. He even introduces his own ethical guidelines: he prefers to eat rude people: the “free range rude” to quote another Hannibal epigram.

Much of the commentary in this documentary is by Jack Levin, a Criminologist with a rather distracting moustache, or perhaps a pet mouse that lives on his upper lip. He sums up the modern cannibal serial killer:

“Many Americans when they think of a serial killer will think of a glassy-eyed lunatic, a monster, someone who acts that way, someone who looks that way. And yet the typical serial killer is extraordinarily ordinary. He’s a white, middle-aged man who has an insatiable appetite for power, control and dominance.”

The standard serial killer appears very ordinary indeed. According to the doco, 90% of serial killers are white males. Many serial killers, we are told, experienced a difficult childhood, abused emotionally, physically or sexually. Hannibal of course saw his sister eaten, and probably innocently joined in the meal, so I guess you might call that a difficult childhood. But of course many people have difficult childhoods (less difficult than Hannibal’s, one hopes) without becoming cannibals or serial killers. Many of these so-called “real life Hannibal Lecters” featured in this program were not even cannibals, such as John Wayne Gacy, who murdered at least 33 young men and boys, but did not eat them, and was not even vaguely similar to Hannibal in appearance, MO, or dining habits. Same with Ted Bundy, who also gets a segment. These killers killed because they enjoyed it – as an act of dominance. Serial killers, Levin tells us, get “high” on sadism and torture. Hannibal, on the other hand, just killed his victims the way a farmer might choose a chicken for dinner – slaughter the tastiest, fattest one, or else the one who has been annoying him.

“There is much discussion as to whether cannibalism is an inherent characteristic in all human beings, our animal impulses, or whether cannibalism stems only from the minds of mad beasts such as some of the most prolific serial killers.” Richard Morgan, narrator.

Eventually, we get to the cannibals. First up is Andrei Chikatilo, the Russian cannibal who sexually assaulted, murdered, and mutilated at least fifty-two women and children between 1978 and 1990. Chikatilo, we are told, liked to cook and eat the nipples and testicles of his victims, but would never admit to eating the uterus – far too abject for his psychosis. Sigmund Freud and Julia Kristeva would find that fascinating.

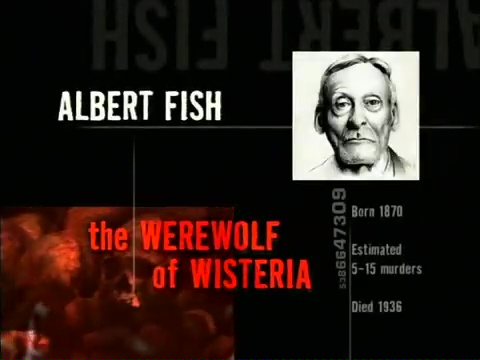

We look in some detail at Albert Fish, the “Gray Man” who tortured and killed probably fifteen children around the US at the beginning of the twentieth century. He mostly specialised in the children of the poor and people of colour, but was eventually caught because he ate a little white girl, causing the police to take the cases seriously at last.

A large section of the documentary is dedicated to Jeffrey Dahmer, perhaps the most famous of the modern real-life cannibals. Dahmer was not a sadist, disliking violence and suffering, so he did not really fit the description used in the doco, and was certainly no Hannibal.

The other experts wax lyrical about cannibals, such as author and psychiatrist Harold Schechter, who speculates that

“Anthropological evidence seems to suggest that cannibalism was a kind of activity that our pre-human ancestors indulged in with a certain regularity, so I think there is probably some sort of innate impulse towards that kind of activity… serial killers act out very archaic, primitive impulses that clearly still exist on some very very deep level.”

Well, that’s definitely not Hannibal, the Renaissance man, who carefully considers each action and dispassionately stays several steps ahead of his pursuers. Jack Levin again:

“Any serial killer who cannibalises victims has broken one of the most pervasive and profound taboos in all of society. Psychologically, this means the killer has achieved the opposite of what he had hoped… in terms of ego, in terms of self-image, he has got to feel worse about himself.”

That certainly is not Hannibal!

But there are some interesting observations in this documentary if we set aside the obvious problems with the comparisons with Hannibal. Zombie flesh-eaters were first popularised in Night of the Living Dead which came out in 1968, what the documentary calls “the most murderous decade” – the 1960s, followed a few years later by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. People flocked to the cinema to see people being eaten because two Kennedys and MLK were assassinated and the brutal, unending Vietnam war was filling the television screens? Maybe so.

Levin tells us

“Most people don’t see the difference between Hannibal Lecter and Jeffrey Dahmer. To the average person, there is no difference between fact and fantasy.“

Col. Robert K. Ressler, who founded the FBI Behavioural Sciences Unit (which makes him a real life Jack Crawford) points out that there are no serial killer psychiatrists, nor do serial killers normally become well integrated into the upper levels of society like Hannibal. So he’s not helping the Hannibal comparison at all. Nor is Levin, who points out that Dahmer was remorseful at his trial, and went out of his way to avoid inflicting pain, unlike most serial killers to whom the killing is a “footnote” to the main text – the torture of the victim. So Dahmer does not fit into the model of serial killer presented here, and he has nothing in common with Hannibal Lecter.

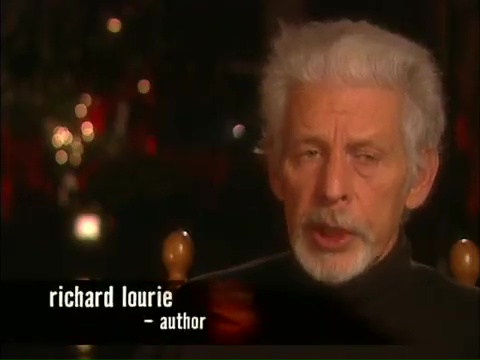

But author Richard Lourie, who wrote a book about Chikatilo, points out that we, the audience, really want to see the serial killer as a Nietzschean Übermensch (superman) – a brilliant criminal genius. He also tells us that Hannibal seems asexual, above the primal drives that motivate people like Chikatilo and Dahmer. Not entirely true of course, if you have read the end of the book Hannibal or read any of the Fannibals’ fan fiction which speculates on some juicy homoerotic episodes between him and Will.

But there is a point to all these rather painfully stretched comparisons between real serial killers and the fictional Hannibal Lecter. Hannibal, Leatherface, the Zombies, are all the inchoate faces of our nightmares, and horror stories are our way of understanding the terrors that fill the news sites. Hannibal is not typical of the real-life serial killer or cannibal, but remember that the apparently kindly old woman who wanted to eat Hansel and Gretel was hardly typical of the horrors of Europe at the time of famine and plague when the Grimms were writing their stories. Each is a facet of horror.

Schechter talks about the simplistic view that cannibalism is in itself “evil”. Which is actually worse, he asks, to torture and kill a person or to eat their flesh when they are dead, an act which can certainly do them no more harm? Indeed.

Levin sums up:

“It could be argued that cannibalism as this ultimate form of aggression lurks within every one of us…. We have an aggressive part of ourselves, it’s part of basic human nature, and to that extent we are all potential cannibals.“

A kind face, a deceptive smile, a gingerbread house or psychiatrist’s couch can sometimes be more terrifying than the sordid crime scenes left by Chikatilo, Dahmer and Fish. The seeming normality of Albert Fish, Andrei Chikatilo, Jeffrey Dahmer or Hannibal Lecter conceals something that we hide deep within our shadow selves.

The full documentary is available (at the time of writing) on YouTube.