“Revenge is a dish best served cold”

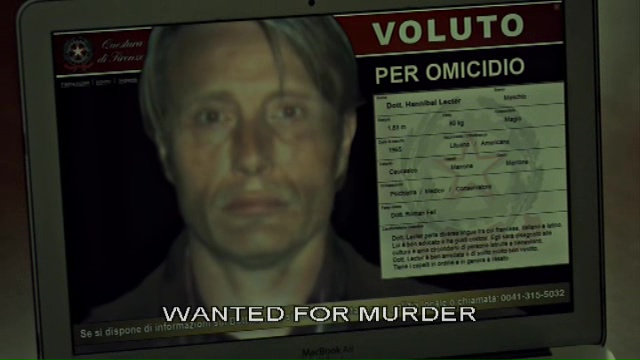

Don Corleone said it in The Godfather, as did Khan Noonien Singh in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, but the saying goes back at least 100 years before that. It doesn’t seem to apply so much in cannibalism movies though, because if you’re really mad at someone, I suppose you’d want him to be warm and watching as you devour him, like Hannibal eating Abel Gideon, after feeding him oysters and acorns and sweet wine to improve his taste. Or Titus feeding Tamora, the queen of the Goths, a pie made of her own sons.

Revenge cannibalism is an exquisite form of retribution, going beyond murder to total destruction of the enemies (or his loved ones), incorporation of their essence, and conversion of their physicality into your excrement. Dante’s Inferno (Canto 33) depicts Count Ugolino in hell, gnawing eternally on the head of Archbishop Ruggieri, the man who had walled him up in a cell with his sons, whom he had eventually cannibalised. Perhaps the earliest narratives of revenge cannibalism appear in Greek legends, particularly that of Thyestes, who was fed the flesh of his sons by his pissed-off brother.

I’m adding this old classic film to the catalogue of cannibal texts as there is some human flesh eaten in anger, although it is not the main course of the film (puns are so hard to avoid in cannibalism blogs). The film starts with a couple of young girls heading to a rock concert, being abducted on the way, raped and murdered. If you are sensitive to such things (I hope most people are) or traumatised by recent news events, you may wish to give this film a miss.

I had forgotten about this movie until the Supernova Festival in which over 260 young people were abducted, raped and murdered, with a savagery reminiscent of that which befalls Mari and Phyllis in this week’s film. The barbaric slaughter of some 1,400 Israelis on October 7 2023 was followed by the IDF’s massive revenge, the extent of which shocked some of the world and impressed the rest. “Well, what would you do?” many online commentators asked.

Well, what would you do if, like the parents of one of the girls, you offered a warm welcome and overnight accommodation to some travellers who, you later discovered, were a gang of escaped criminals who had raped and murdered your child? The film answers that with a shotgun, a chainsaw, and an electric booby-trap.

Not what the UN would call a “proportionate response” (whatever that means), but many in the audience cheered at each gruesome death when it finally made it into cinemas (not until 2004 in Australia). Oh yes, one other form of killing that qualifies this otherwise simple slasher as a cannibal film—the girl’s mother, Estelle, pretends to seduce one of the gang members, then bites off his penis and swallows it.

The film critic Robin Wood spoke of what he called “the return of the repressed”. We repress our animal instincts to live in community, but beneath that veneer of respectability and normative morality lies “the monster”, the one we take out to exercise in the comparative safety of the cinema screen. Horror films such as this one depict the overcoming of repression, the shedding of the façade of respectability, in both the escaped psychopaths and then the vengeful parents, who shed their polite decorum to slash and kill. Craven shows the same thing in his later movie The Hills Have Eyes. Films from the seventies routinely explored a moral equivalence, a Vietnam War era pacifism that assumed any violence was equally appalling. Cannibal Holocaust, made at the end of that decade, sums up this view of the cycle of violence and the moral degeneracy of revenge when the anthropologist asks, “I wonder who the real cannibals are?” Later films from more cynical times tended to depict the killer or cannibal as either an irredeemable monster or a heroic figure, taking on bankrupt social imperatives. Right and wrong has come back into fashion but divides the viewers, depending on what their social media bubble tells them.

The film starts with a statement that it is a true story, which I guess used to be all the fashion—think Punishment Park, Cannibal Holocaust and the Blair Witch Project. The good old days, when truth was optional… oh forget I even started that sentence.

Anyway, this film wasn’t a true story, it was a remake of Ingmar Bergman’s 1960 film The Virgin Spring, in which a father takes merciless vengeance of a group that has raped and murdered his daughter. That was in turn based on a mediaeval Swedish ballad called “Töres döttrar i Wänge” (“Per Tyrsson’s daughters in Vänge”) in which the vengeful father discovers that the rapists he has just killed were actually his sons, sent off by him into the cruel world.

But it was Wes Craven’s film that introduced a bit of cannibalism into the revenge recipe. Wes Craven is best known for the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise and the first films of the Scream franchise. Last House on the Left was his first feature film, and he had such low expectations of its success that he felt he could be as outrageous as he liked and no one would ever hear about it, particularly his conservative family. But it did a lot better than he expected, to the extent that,

“I literally had people who would no longer leave their children alone with me. Or people that would, when they found out I had directed the film, say “That was the most despicable thing I had ever seen,” and walk out of the room.”

Audience members would get into fistfights, have heart attacks, and in many cases invaded the projection room to slash the film. Well, consider yourself warned.

Craven decided he would avoid horror, but was a complete failure at his attempts at more socially acceptable work. He had become known as the master of the slasher, leading him to another revenge cannibalism film in 1977 which became a cult classic, The Hills Have Eyes, in which a group of mutant cannibals kidnap, rape and slaughter (and eat) a ‘normal’ American family, who then inflict massive retaliation on them, adopting their savagery and raising the stakes.

In early 2023, a viral video seemed to show a couple of hunters gloating over a lion they had killed, and then being attacked and eaten by another lion, supposedly the dead lion’s brother.

Well, what would you do?