Peter Jackson is a New Zealander, and the fourth-highest-grossing film director of all time, behind only Spielberg, Cameron and the Russo brothers. He is best known for The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit trilogies, as well as movies like King Kong and the documentary The Beatles: Get Back.

But we all have to start somewhere, and Jackson’s first feature was Bad Taste, a splatter comedy which took years to make as it began life self-funded and only later received a grant from the NZ Film Commission. Many of Jackson’s friends acted and worked on it for no charge. Shooting was mostly done on weekends since Jackson was then working full-time for a newspaper in Wellington, the NZ capital.

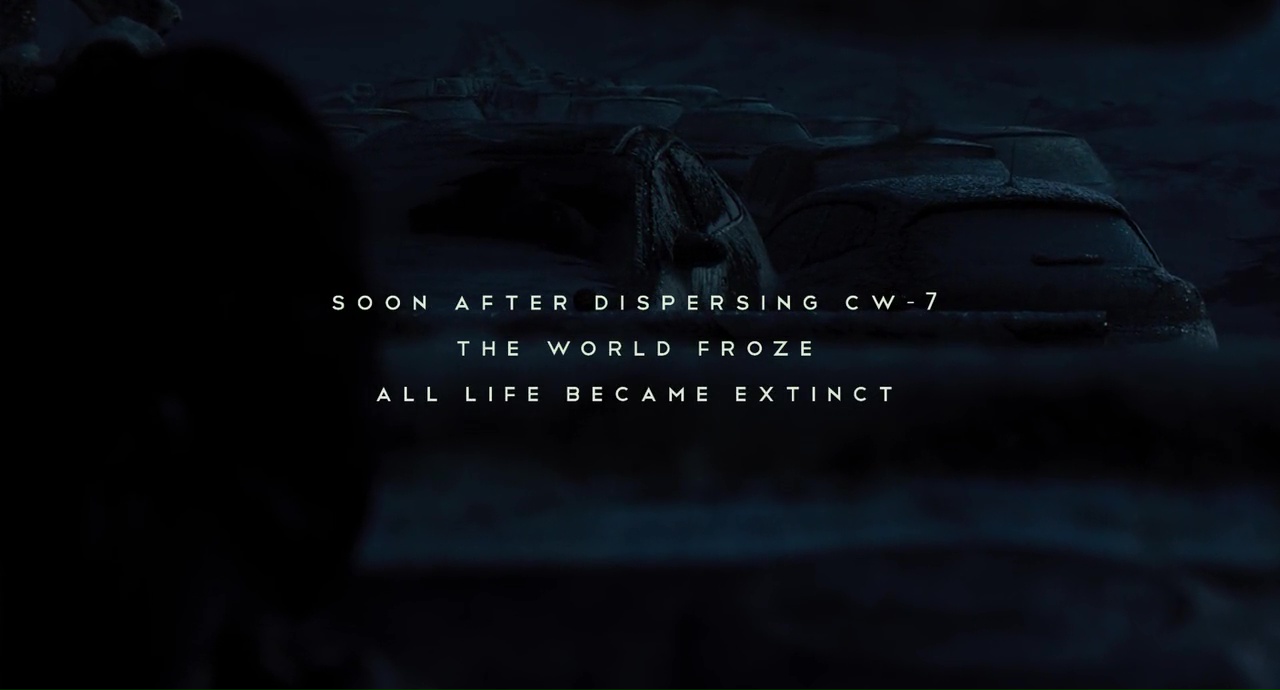

Bad Taste is about aliens who plan to capture humans for food. They take over a (fictional) NZ town called Kaihoro (which means something like “fast food” in Maori) and butcher all the residents.

“There’s no glowing fingers on these bastards. We’ve got a bunch of extra-terrestrial psychopaths on our hands.”

It turns out that they are not just hungry but entrepreneurs from the “Crumbs Crunchy Delights” company, and need to collect human flesh for the home planet market, and get it there before competing alien corporations.

“I am certain that when the Homo sapiens taste takes the galaxy by storm, as it will, Crumbs Crunchy Delights will be back at the top”

They are disguised as humans until they drop the pretence and, luckily for us, they speak English to each other to reveal their plans. Their plans are foiled by a team of agents from the Astro Investigation and Defence Service (AIDS) entering the town to take down the invaders.

The action sequences are actually very well done, long before Jackson had access to special effects studios, with choreographed fight sequences and buckets of gore and brains and other body parts. Jackson took two roles, a nerdy scientist who is a member of the government agents, and a leader of the aliens, including a famous scene in which he fights himself on top of a cliff.

The film is most famous for its unapologetic gore, including half-eaten bodies, heads coming off, and brains leaking out of skulls. The brave Kiwis mow the aliens down in an interminable gun-fight, which culminates in Derek (Jackson) killing the alien leader, Lord Crumb, by jumping on him from the floor above while wielding a chainsaw, a favourite of cannibal films, cutting the alien’s body in half and disappearing inside the corpse. The film was banned in Queensland briefly, which did wonders for its publicity; the video release proudly proclaimed on the cover “Banned in Queensland”.

But is it cannibalism? It is after all a completely alien species from another world eating humans, or at least trying to. So not strictly cannibalism, but humans being eaten by aliens dressed as humans is a popular narrative in science fiction texts (see for example Under The Skin), and raises some interesting questions. Anthropocentric humanism maintains that we are somehow on a higher level than “animals”, even though we are animals, a species of Hominidae (Great Apes). Because of this ontological division, bolstered in past centuries by religious beliefs about humans being made in the image of the divine, we tend to judge other animals as possessions, inferior beings to whom we can do as we wish, so we kill them, skin them, shear them, eat them, experiment on them, race them, and so on. Not just other animals; the colonisers of Africa, South America and other parts of the world felt the same way about the indigenous peoples who lived in the areas they coveted, and so they were conquered, enslaved, converted or simply exterminated.

What if travellers from another planet, considering themselves far superior to us (not an entirely unreasonable proposition if they have conquered deep space travel), decide to colonise, exploit or even eat us? If we could take them to the Galactic High Court, the learned judges might rule that the aliens were simply doing to us what we do to billions of other earthlings each year. As John Harris wrote:

Suppose that tomorrow a group of beings from another planet were to land on Earth, beings who considered themselves as superior to you as you feel yourself to be to other animals. Would they have the right to treat you as you treat the animals you breed, keep and kill for food?

Bad Taste is well made, entertaining and, if you are not worried by lots of gore and brains, very watchable. It debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1987, which is not bad for a first movie, a splatter comedy, made on a shoestring. It currently has 71% “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes, which is far better than many far better financed films. A number of critics made great sport of the title, saying that “bad taste” described the film well, but that was deliberate, a clever combination that tells the audience that it is bad taste cinema (may leave a bad taste in your mouth) and that human meat tastes bad, which according to all the cannibals who have testified about it, is simply not true. We taste somewhere between veal and pork, and would certainly be very popular in galactic fast-food joints.