In 1987, Japanese student Issei Sagawa murdered a young Dutch woman, Renée Hartevelt, a fellow student at the Paris Sorbonne, then mutilated, cannibalised, and performed necrophilia on her corpse over a period of two days.

Sagawa was declared insane in France and returned to Japan, where he could not be tried for murder as no evidence had been sent by the French. A free man, he became something of a celebrity, making torture porn movies, selling paintings (many of them nudes), writing books and manga showing his crime, and even becoming a food critic. The fascination so many people feel with the life and crimes of Issei Sagawa is shown by the number of documentaries made about him:

- Cannibal Superstar (Viasat Explore, Sweden, 1986, 47 minutes)

- Excuse Me for Living (Channel 4, UK, 1993, 60 minutes)

- The Cannibal That Walked Free (Channel 5, UK, 2007, 46 minutes)

- Interview with a Cannibal (Vice, US, 2011, 34 minutes)

And, most recently, this one: Canniba, made by two artists/anthropologists, Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor from Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab. Unlike the more standard documentaries which deal in psychoanalytic speculations and dramatic narration, this one is an extreme close-up of the cannibal himself, in his declining years. The only characters shown are Sagawa himself, his brother Jun and a young woman carer, who is inappropriately dressed in a maid’s uniform and happily tells him zombie stories as she prepares him for bed. Sagawa was hospitalized in 2013 from a cerebral infarction, which permanently damaged his nervous system, and due to this and severe diabetes is largely unresponsive through most of the filming, becoming animated only when discussing his murder of Renée. Jun sums his brother up:

“Cannibalism is really very much nourished by fetishistic desire. The desire to lick the lips of your lover, and things like that, are based on primal urges. Cannibalism is just an extension of that. Both extremes exist within him. Cannibalism is a totally different world for him.”

The film seems to ask us to consider our own fetishes (you don’t have any? That would make you unique) and asks whether we are repulsed by Sagawa’s acts, or by the abjection in ourselves which he forces us to confront.

The first thirty minutes are a gruelling close-up of the two men – Issei and Jun and their desultory interactions, with the camera so close you can see every pore, except when it (blessedly) goes out of focus. Issei is largely catatonic, staring sightlessly as we, in turn, stare in extreme close-up at his face, which looks almost like a death mask. The only signs of animation are when he is offered chocolate, of which he seems inordinately fond, perhaps as a substitute for the human flesh he so craved. Probably not great for his diabetes, but we’re not really hoping for a happy ending to this story.

Unable to see a future, Issei dwells on the past. He remembers his mother telling him in graphic detail about falling down some stairs in a department store and miscarrying.

From this glimpse of the behavioural background to his subsequent actions, we are suddenly catapulted to a clip of a much younger Issei in a porn film, biting a woman’s buttocks, as he did to the dead victim, then being urinated on and finally masturbated by her.

The horror of his ruined visage is contrasted to the prudish pixilation of the debauchery.

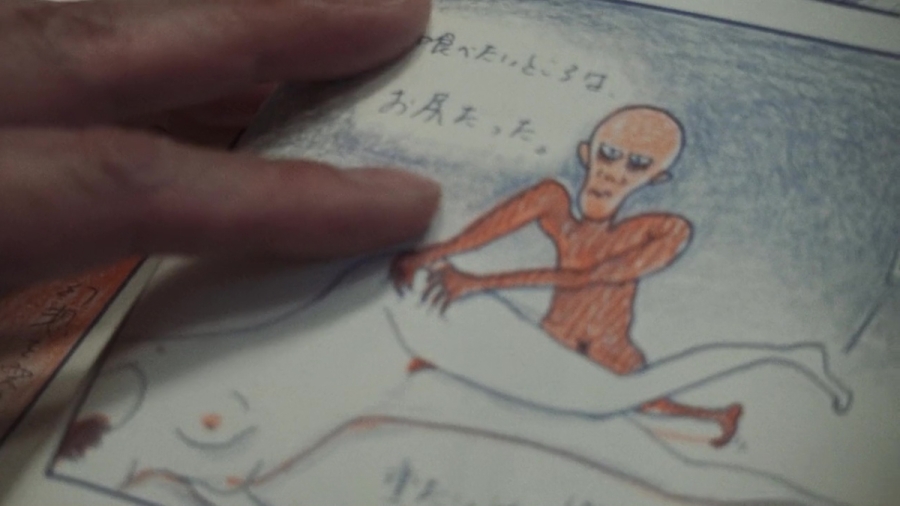

If we haven’t walked out by now, as many of the audience did at the early screenings in the Toronto and Venice film festivals, we are then treated to his commentary, now quite animated, on his manga – a comic-book format showing his murder, rape and cannibalisation of the young woman. His brother tut-tuts throughout, saying he doesn’t want to see such things, while Issei explains what he did, and what it meant to him.

“For a hideous person like me, she was out of reach.”

A bullet in the back of her neck was the only way he could think of to bring her into his reach.

“Finally the thing I was craving to eat was right in front of me! The stench doesn’t matter. I started with the richest part of her right buttock.”

The murder and cannibalism turned a shy, diminutive man-child into a fierce Samurai, in his own mind.

He describes the eating the flesh (the harvesting of which is shown in detail in the manga) as “an historical moment!” For that brief time, the woman was entirely his, and what Derrida called carnivorous virility gave him an absurd sense of masculine power as he “dominated” the woman’s corpse for his sexual and gastronomic pleasure.

There’s heaps more, but you’ll have to watch the film or get the manga – my blog has its limits.

The film then disconcertingly lurches into home movies of the two men when they were cute little boys.

We are not given a commentary, but we know from other accounts that their uncle would dress up as a cannibal and capture them for his cooking pot. The psychoanalysts would eat that up, but we should consider that many of us are chased by various demented relatives in our childhood games without going on to become monsters in their likeness.

Issei’s brother Jun, now his carer, appears as the sane one in the family, but we are quickly disabused of that as we see his own self-abuse – he likes to wrap his arms in barbed wire, and cut his arms with knives. Everyone needs a hobby I guess. Issei is not impressed – compared to shooting a woman from behind and then having sex with the body and eating parts of it, a bit of cutting would seem fairly tame to him.

Finally we meet the carer, a young, attractive women dressed as a maid. This is actually Satomi Yôko, an actress playing a maid playing a carer, a further jolt to our fragile sense of reality. She giggles over Issei, telling him, as he stares into her breasts (a particular fetish of his):

She asks him if he wants to cosplay a zombie, and tells him a convoluted story about a zombie woman who eats the old man who keeps her in chains, a reversal of his history, and another fetish of Issei’s, who early in the film says “I want to be eaten by Renée.” She tells him:

“For the zombie to survive, I have to keep eating live humans… I’m alive, but I can’t be with normal humans.”

It’s a perfect summation for the fate of Issei Sagawa.

The only soundtrack is at the very end, The Stranglers’ 1981 song “La Folie” (“madness”) which concerned Sagawa’s crime.

It’s in French, but the partial translation is:

He was once a student

Who strongly wanted, like in literature,

His girlfriend, she was so sweet

That he could almost eat her

Rejecting all vices

Warding off all evils

Destroying all beauty

The film managed 53% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, while the New York Times called the movie “an exercise in intellectualized scab-picking.” IndieWire summed up:

“Caniba” ranks among the most unpleasant movies ever made, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t see it.

There is another review of an earlier Sagawa documentary, The Cannibal That Walked Free on my blog. The film Caniba is available, if you are so inclined, from https://grasshopperfilm.com/film/caniba/

Pingback: Issei Sagawa: THE CANNIBAL THAT WALKED FREE (Toby Dye, 2007) – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: The Butcher of Plainfield: ED GEIN (Chuck Parello, 2000) – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: Is “true crime” really “true”? INDIAN PREDATOR: DIARY OF A SERIAL KILLER (Netflix, September 2022) – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: Conversations with a Killer: THE JEFFREY DAHMER TAPES (Netflix 2022) – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: Cannibalism as eating disorder: FEED ME (2022) – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: ISSEI SAGAWA – “the Kobe Cannibal” – DEAD at 73 – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: Issei Sagawa: “This Is A Manga Written By A Cannibalistic Murderer” – The Cannibal Guy

Pingback: Deep tissue cannibalism: THE HORROR OF DELORES ROACH Episode 1 (Aaron Mark, 2023) – The Cannibal Guy