Let’s get this out of the way – there is nudity. Lots of it and throughout the movie. Well, it’s set in pre-colonial Brazil, and the Indigenous peoples did not bother with a lot of clothes, so it’s historically accurate. To ensure authenticity, the actors and the crew were all naked, so that nudity would become natural. If that bothers you, please read the blog but skip the movie.

While it was refreshingly authentic, the nudity was also a problem. First, because the authenticity is somewhat diminished, as The New York Times critic pointed out, by the fact that the natives are “middle-class white Brazilians… stripped down and reddened up for the occasion”. Secondly, the film was refused entry to the Cannes Film Festival because of all the swinging dicks. In Brazil, the censors were eventually persuaded that the natives indeed did walk around naked, but remained vehemently opposed to the nude Frenchman, a telling comment on the racist distinction that the film was intending to expose.

So, the plot in a nutshell: the French and the Portuguese are fighting to control the rich lands of South America. Each has allied with local tribes who are at constant war with each other, often involving (so the European narrative goes) capturing and eating each other’s warriors. The Tupinambás are allied with the French, while the Tupiniquins are allied with the Portuguese. The Frenchman of the title escapes his own command, is captured by the Portuguese, and is then captured by the Tupinambás, who are allies of the French, but believe him to be Portuguese, so intend to eat him. Got all that? – there will be a test.

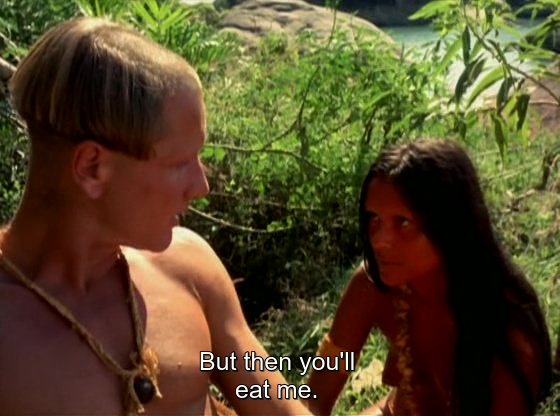

Tupi custom involved bringing the captive into the community, feeding and homing him, and even finding him a wife, then eventually killing him in a ceremony that will allow them to capture his essence, bravery, speed, and so on.

This wide-spread belief about the Tupi comes from a European who was captured but then escaped in 1554, came back to Europe and wrote a book. His name was Hans Staden, and he was actually a German who was trying to get to India. But since it was the French who were invading South America at the time, the director changed his nationality.

De Bry’s engravings of Tupi cannibalism were “eaten up” by the Europeans.

Tupi cannibalism has a whole literature explaining it or denying it – William Arens claimed the ‘evidence’ was mostly based on Staden’s account, which contained several contradictions, and had been continually retold as if it had happened to new re-tellers. Other anthropologists such as Rene Girard explained Tupi cannibalism as a seamless explanation for the way culture and religion have evolved. The universal violence of the human species is redirected toward the outsider, who is taken into the tribe, but remains foreign enough to be killed as a scapegoat, to release the social pressure that would lead to endless internal revenge feuds. For many, Jesus became the ultimate scapegoat under this theory, even to the extent of insisting that his followers eat and drink wine and bread transubstantiated into his “blood and body” in the Eucharist ritual.

For my flesh is meat indeed, and my blood is drink indeed.

John 6:55

The Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro proposed a ‘post-structural anthropology’ in his book Cannibal Metaphysics. De Castro sought to ‘decolonise’ anthropology by challenging the increasingly familiar view that it was ‘exoticist and primitivist from birth’, denying that cannibalism even existed, and so transferred the conquered peoples from the cannibalistic villains of the West into mere fictions of colonialism. Arguing that the ‘Other’ is just like us is to deny any separate identity and to return the focus of anthropology to that which interests us: ourselves. Rather than deny the existence of cannibalism, which allows a reclassification of the Amerindian peoples as like the colonialists, de Castro examines the details of Tupinamba cannibalism, which was ‘a very elaborate system for the capture, execution, and ceremonial consumption of their enemies’. This alternative view of Amerindian culture rejects the automatic assumption of the repugnance of cannibalism, which serves to either confront it or deny its existence.

Well, that’s pretty much where this film planned to go. Pereira dos Santos challenges the Eurocentric perspective which insists on a superior civilisation overcoming a primitive one. It is true that Tupi civilisation was destroyed by the slavery, smallpox and slaughter of the Portuguese who, the film tells us at the end, also wiped out their allies the Tupiniquins. The Tupi peoples are now a remnant, confined to small areas and currently being decimated by COVID-19.

But the chief, in the killing ceremony which promises the Frenchman’s body parts to his relatives (his wife will get his neck), tells the story as a mirror image:

“I am here to kill you. Because your people have killed many of ours, and eaten them.”

So the film asks: who were/are the cannibals? It does not fully succeed in telling this story, because the audience gets involved with the Frenchman’s story, instead of his captors. Pereira dos Santos lamented that the public:

“…identified with the French, with the coloniser. All spectators lamented the death of the hero. They did not understand that the hero was the indigenous, not the white, so much were they influenced by the adventures of John Wayne.”

Nonetheless, the binary of the colonised and the powerless occupied victims is so deeply embedded in our cultural stories that it is refreshing to see this mirror image version, where the indigenous win the battle, if not the war.