Screams, smashed skulls, flying flesh were not what villagers of an Uttar Pradesh village expected on a quiet Monday morning when a 30-year-old labourer brutally murdered his wife and mother on the rooftop of his house and then chewed flesh from their smashed skulls as his neighbours watched.

A 30-year-old man was arrested on 12 January 2026 in Kushinagar’s Parsa village for the double murder of his mother and wife. The suspect, who has been identified as Sikandar Gupta, had returned to the village about a month previously after working as a labourer in Mumbai. According to police reports, the victims were identified as his wife, Priyanka (28), and his mother, Runa Devi (60). Gupta initially attacked the victims with wooden sticks, and then with cement bricks, causing fatal head injuries to them.

Local residents rushed to the scene as the screams of the women echoed through the neighbourhood. Witnesses reported seeing Gupta mutilate the bodies and consume portions of the remains. When the crowd attempted to stop him, Gupta began throwing pieces of debris and human flesh at them, which caused widespread panic until the Ahirauli police arrived to detain him.

Kushinagar Superintendent of Police, Keshav Mishra, said that,

“a case of double murder was registered, and police are also examining the accused’s mental condition as part of the investigation.”

Neighbours informed police that Gupta had a history of substance abuse involving alcohol and cannabis and was known for frequent domestic disputes. The accused remains in custody pending a formal psychiatric evaluation to determine if he is fit to stand trial or if the murders were the result of a total psychological collapse.

Gupta has been admitted to the Psychiatry Department at AIIMS (All India Institutes of Medical Sciences) under police custody. According to reports, Gupta is speaking incoherently, at times claiming he was drunk during the incident and at other times saying he does not remember anything at all. Doctors have sedated him due to aggressive behaviour and are closely monitoring his condition.

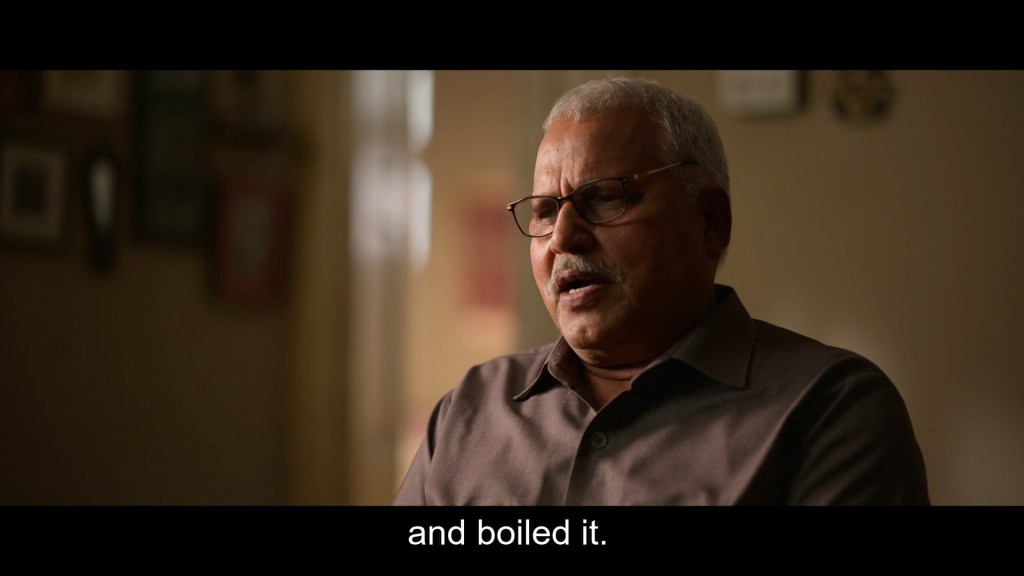

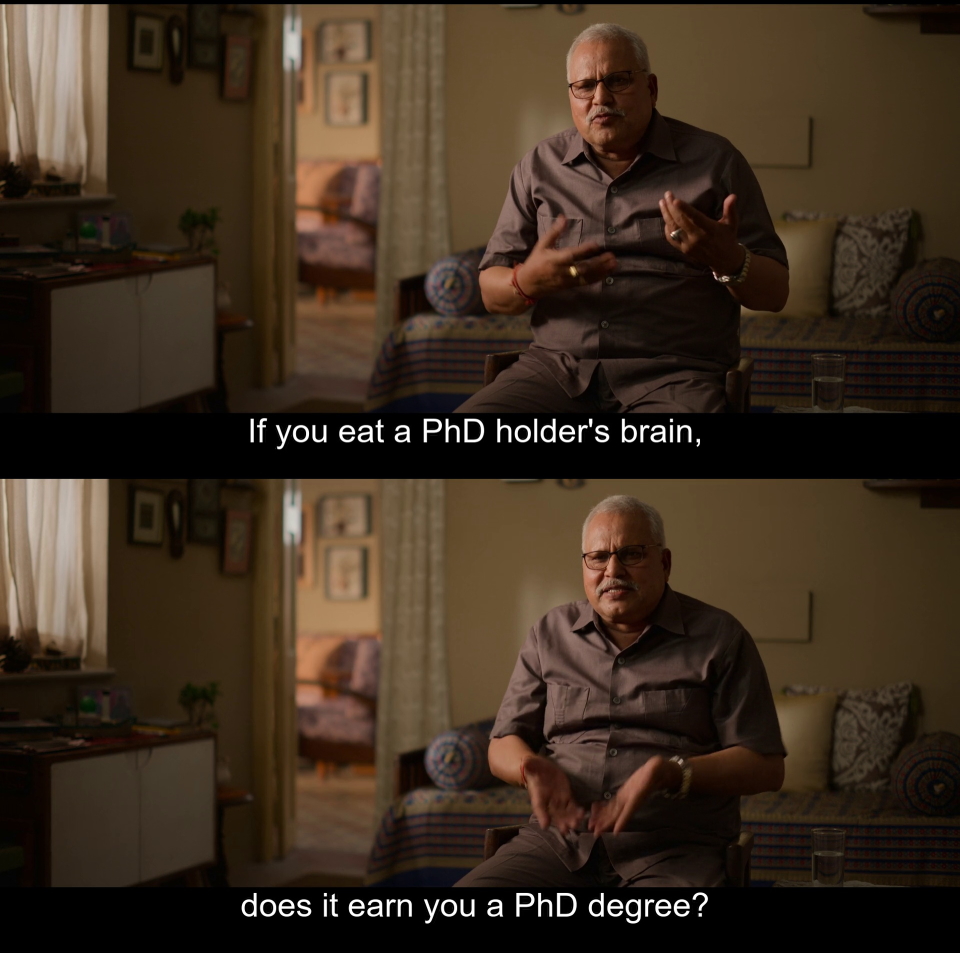

Experts suggest the violence points to deep-seated psychological issues. Dr. PK Khattri, a senior clinical psychologist in Lucknow, said that Gupta’s agitated and non-communicative behaviour “points toward a severe psychotic break” that led to cannibalism.

As Dr Watson used to say, “No shit, Sherlock!”

Ashok Srivastava, an independent criminologist and an associate of the National Forensic Sciences University (NFSU), said that such extreme acts often stem from a

“desire for total domination”

He added that this type of behaviour represents an “ultimate expression of control, often triggered by internal frustrations or extreme psychopathology.”

Which could be said of human societies generally. From bullying in school to sexual abuse to war atrocities to the commercially pressured obsession with eating the flesh of other animals, appetites are driven by this “desire for total domination”, of territory, of food, and of the bodies of others. Anthropocentrism, sometimes called speciesism, is maintained by the practice of killing other animals in ever increasing numbers, to prove our superiority and deny our own animality and mortality. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida called that “carnivorous virility”, the sacrificial slaughter and consumption of “inferior” animals by the rational, patriarchal civilised meat-eater.

What happens when the lust to dominate or kill outruns the limits of anthropocentrism and is instead turned back on fellow humans? The biological fact is that humans are animals, and animals are made of meat. When a society reaches a point where the old ethical agreements are disintegrating, it can either forge new ones or dissolve into chaos, war and, yes, cannibalism. The psychopath, such as the one in this case who allegedly started his brutal rampage with domestic violence before turning to murder and flesh eating, seems to understand this better than most ‘sane’ people.