According to Hollywood, everyone eagerly anticipates Christmas, which must be why incidents of violence flare over the festive season (largely driven by festive booze). Christmas goes for twelve days (they tell me), which covers the New Year mayhem as well, and reportedly involves a lot of odd things like lords leaping and pear trees containing medium sized birds. This film covers the twelve days, but omits French hens and turtle doves, etc, in favour of lots of blood and gore. I reviewed it many years ago, but it seems worth a fresh “bah humbug” as I recover over my keyboard after battling greedy retailers and stressed-out motorists.

“Bah! Humbug” always seems like a pretty good response to the confected cheer of Christmas, particularly to those who do not, for various reasons, celebrate the event or conform to the voracious consumerism that accompanies it. If you are one of the many who is over the Christmas rom-coms and tear-jerkers, you may have already come across the German Christmas demon Krampus, who appeared in a 2015 movie from Michael Dougherty, involving goblins, killer toys, malicious snowmen and a jack-in-the-box that eats a child whole, although he has been punishing naughty children for a lot longer than that, and may date back to pre-Christian folklore.

The cannibal movie reviewed today, though, was originally called The 12 Deaths of Christmas and features a different villain – a Christmas witch named Frau Perchta who, according to legend, steals a child each of the twelve nights of Christmas. The witch is also said to slit open the bellies of disobedient children (not dissimilar to the threats of cannibalism which Andre Chikatilo’s mother used to keep him in line). The film’s name was changed to Mother Krampus for the American audience, many of whom have adopted Krampus as a sort of anti-Santa. Frau Perchta does not have nearly the same fan base.

The Santa Claus dogma is of course about socialisation – children are told that a large stranger will sneak into their houses at night and reward them if they are “good”. What if they are not good? Who will sneak into their house then, and what mayhem will ensue? Krampus was one answer, Frau Perchta another. Then there was Santa’s assistant, Père Fouettard who, in a nod to the suffering energy corporations, hands out lumps of coal to children who are not deemed to have been good, and sometimes whips them too (the name Père Fouettard translates as “Father Whipper”. Following Santa around appears to have been his punishment for engaging in a bit of entrepreneurial cannibalism, in which he and his wife drugged three children, slit their throats, cut them into pieces, and stewed them in a barrel, to be sold as Christmas hams. The taste, allegedly, is almost identical.

But today’s film is not just about stealing the bad children, and perhaps killing them, no, it’s all about the punishment of the wicked being extended to the following generations – a popular theme in the Bible (check out Deuteronomy 5:9 for some unfair shit). Perchta is coming for the children of adults who wronged her.

One of these children, and the protagonist of what passes for the plot, is Amy (Faye Goodwin – Mandy the Doll). Her mum is Vanessa (Claire-Maria Fox of Suicide Club and Bride of Scarecrow), and Vanessa’s dad – Amy’s grandpa – (Tony Manders, from The Young Cannibals) lives outside the village, near a scary forest in Belgrave (the UK one), and asks her to drive him, on Christmas no less (no Ubers I guess) to the Church, where a bunch of locals want to discuss the focal local issue – lots of village children are disappearing. There we finally get to hear the legend of the witch:

“Frau Perchta was a witch, who over Christmas stole the souls of children.”

Dad admits to Vanessa that the peaceful villagers got together to kill an old woman 25 years ago. We, the audience, know the background, through an endless voiceover accompanied by cards at the start of the movie. 12 kids disappeared over the 12 days of Christmas in 1921, and none were found, except for one girl whose mind was gone, and she could only scream “the witch! The witch!”

Then, in 1992, five more kids disappeared, their bodies were found in the forest, and the villagers believed, for reasons far from clear, that a nice old lady was the killer and was in fact Frau Perchta the witch, so they stabbed her and lynched her, as you do if the local constable is on leave, in a backward and primitive town like Belgrave, which apparently hosts the National Space Centre!

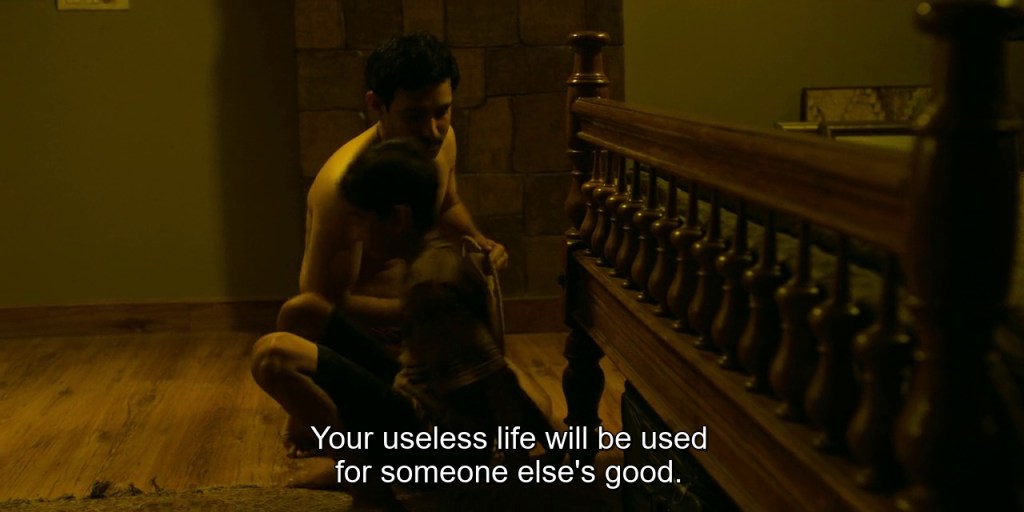

But as she died, she shouted a curse – that Frau Perchta would be back to wreak revenge on them, and their children. So, maybe she wasn’t quite so nice. Yeah, that’s about it for plot – we see (several times) the stringing up of the old woman, we see the risen witch. The witch kills lots of people in creative ways, including one who is cut up and made into a Christmas light show, another whose flesh is pressed into a cookie cutter to make Christmas peoplebread men, while another is trussed up like a Christmas turkey with an apple in her mouth and carved up, and her flesh cooked and fed to her boyfriend, who is Amy’s absentee dad. Then dad has his heart pulled out and eaten (not uncommon in cannibal stories – think Fresh Meat or even Hannibal).

The climax of a horror film (or any action movie) is usually the last ten minutes, in which the story is resolved and the bad guy defeated (until the sequel). This one goes on (and on and on) for about half an hour, presumably to ensure the film is considered a full-length feature, and it resolves nothing much, with a twist at the end that makes no sense at all. But lots of people get killed, and several have parts of them eaten, which is enough to get a mention in this blog, I guess. The plot is thin, the acting is often appalling, the continuity director in some parts seems to have been taken into the forest and eaten. But it’s presented as a low-budget slasher, and that’s what they are often like – they are not dramatic masterworks, but gruesome pantomimes. The idea of one child’s aunt walking him home through the dark forest at night when bodies are turning up everywhere is narratively absurd but, in a panto, we want to anticipate the villain, we want to guess what is going to happen, and yell at the actors to “look behind you!” And the gore, and the fright factors, are quite well done.

The moral of the story, if there is such a thing, is pronounced by a mysterious woman who turns out to be Amy’s grandma, not that it does her much good.

“Taking it into our own hands, playing God. That’s why all this is happening.”

Isn’t that exactly what humans do – play God? Nietzsche told us that God is dead, we killed him, so we have to become God. We play God in so many ways – the Christmas story in essence is about a Jewish family trying to escape one of the many psychopaths who have played God over the centuries. We play God when we nominate ourselves as above nature, more angel than animal, and proceed to destroy our own ecosystem. Who bears the suffering from such follies? The children. Like Frau Perchta, our vicious brutality usually comes back to haunt us, through the generations.

At the time of writing, the full movie (should you wish to bother) is available on YouTube.