What’s leading the news? Wars roiling the globe? Economic dislocations? Warnings about possible new and very nasty pandemics?

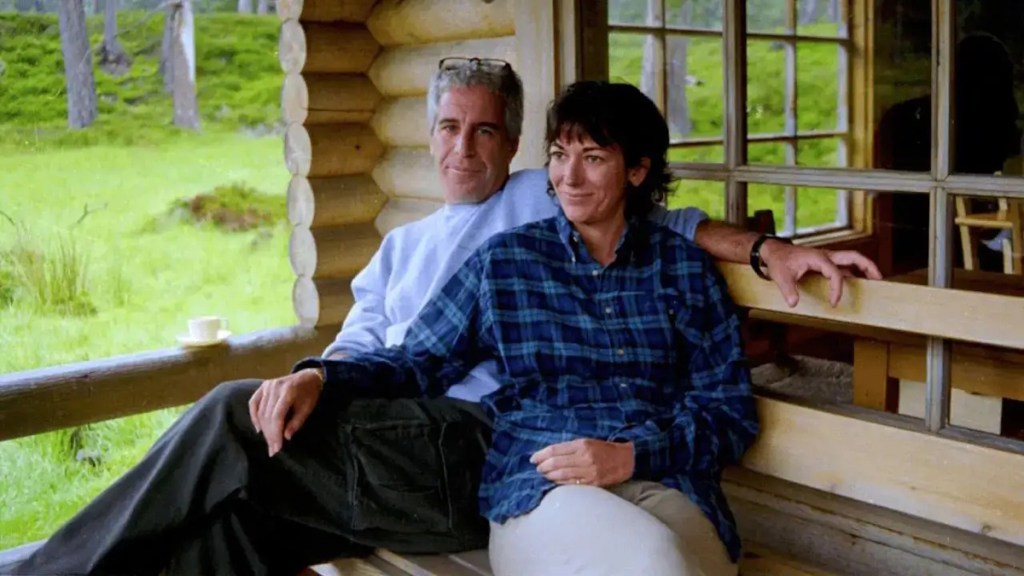

No. All anyone seems to want to talk about is Jeffrey Epstein, the late financier and convicted sex offender, and the millions of pages of documents and photos that are being released (the latest and final batch on January 30) by the US Department of Justice in a hodgepodge of verified or dubious forms, some heavily redacted.

Claims are now circulating online that Jeffrey Epstein engaged in cannibalism or, to be more precise, “ate babies”.

One document, cited by online users, contains allegations that babies were dismembered and their remains consumed. The same document makes a reference to “George Bush 1”. However, the claims have not been substantiated, and their origins remain obscure.

Babies are the first choice of predators and scavengers like humans, because they are easier to catch and their meat more tender. Think of how “lamb” or “veal” sell at a premium to “mutton” or “beef”, how “suckling” pigs are a delicacy, or how so-called “broiler” chickens are killed and eaten at six to seven weeks old. As Curtis says in the movie Snowpiercer:

Some have even suggested, satirically, that eating babies would be a good thing for the environment.

The allegations have been further amplified by the resurfacing of a video from 2009 featuring Gabriela Rico Jimenez, recorded in Mexico. In the clip, Jimenez alleged that she attended a private gathering of wealthy individuals where she witnessed cannibalism.

This story was covered by this blog some months ago, when it last made the rounds due to an exposé on a podcast called Mexico Explained. The blog about her is linked here.

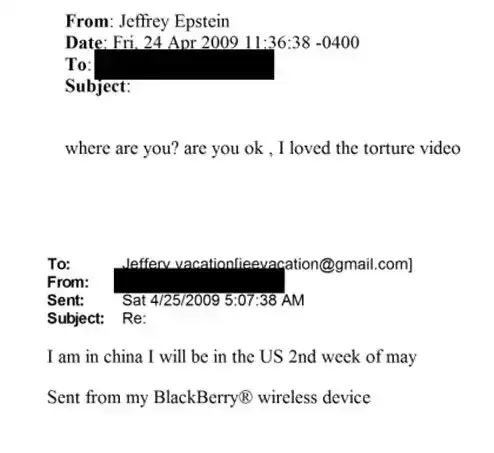

Interest in Jiménez’s case has now surged again, after newly released Epstein documents referenced a party on a yacht and included allegations involving extreme behaviour. One email allegedly sent from Epstein’s known email address read:

“Where are you? Are you okay? I loved the torture video.”

These references, revealed as part of the January 2026 document release, sparked widespread public concern and renewed online theories linking Epstein’s network to past claims made by Jiménez. The material has led many online to speculate on connections between the Epstein files and Jiménez’s 2009 accusations. While no new verified information has emerged about Gabriela Rico Jiménez’s whereabouts or fate, the mystery surrounding her disappearance continues to enthral internet users worldwide. However, there is a dearth of concrete evidence linking her allegations to Epstein.

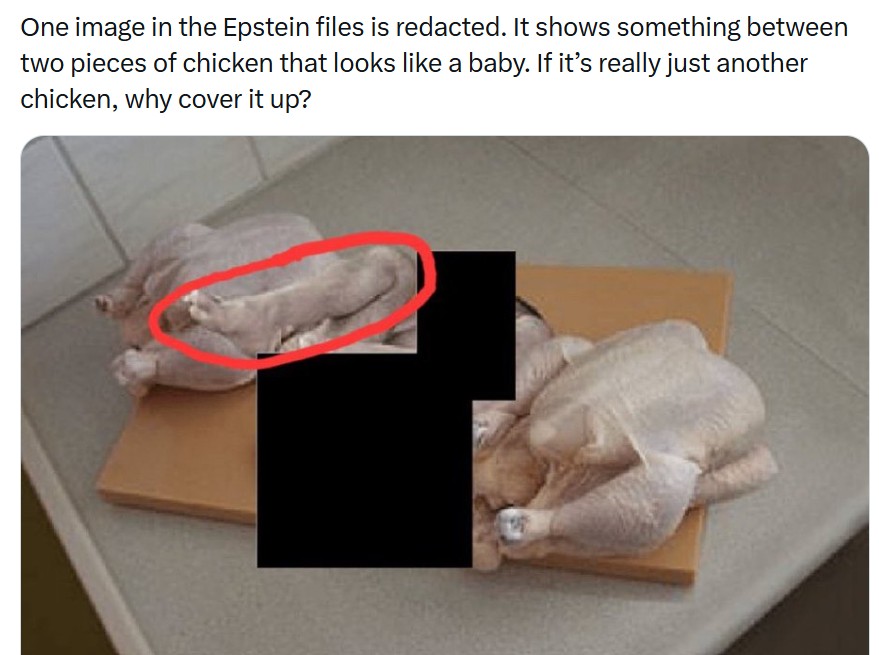

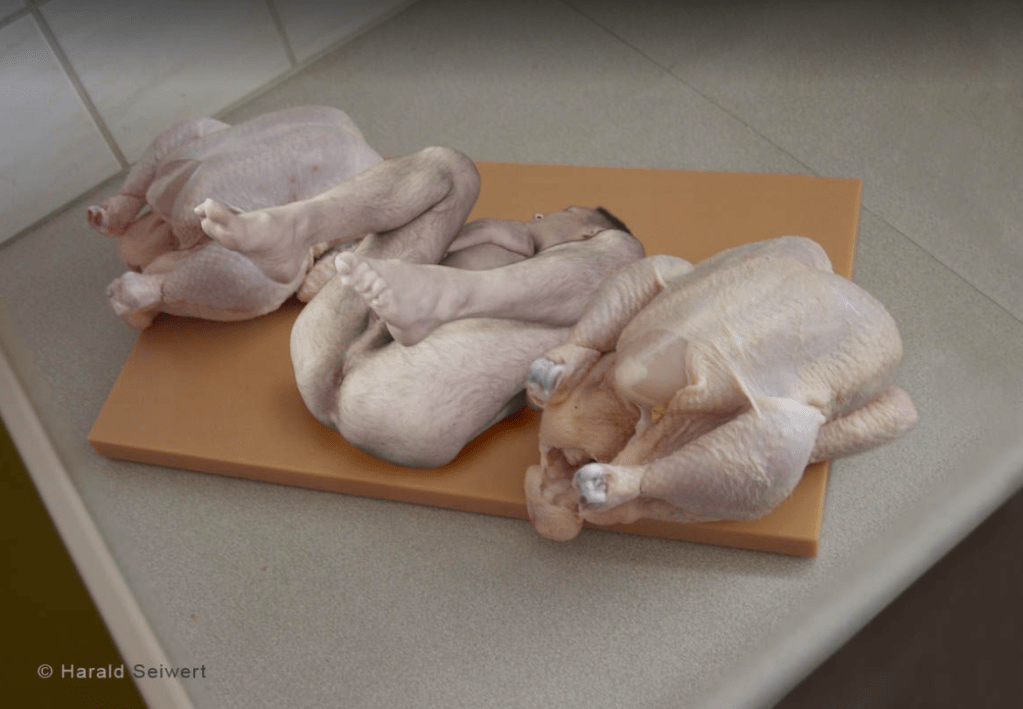

Social media users have drawn further conclusions from unrelated material, including an image (heavily redacted) that they claim emerged from the Epstein files showing a baby among chicken corpses. Observers have noted that the photograph was actually an art work from 2003 by a German artist named Harald Seiwert, used in vegetarian campaigns.

Why cover it up? Well, maybe because it was showing a guy’s hairy bum. Here’s the original:

Several posts on X have promoted conspiracy theories in response to the files. Others are circulating (again) a long-debunked image, clearly a deepfake which first appeared in 2023, purporting to show Epstein with young boys from a rap duo called “Island Boys”, Alexander (Alex) and Franklyn (Franky) Venegas. Some are even claiming the twins are Epstein’s children. However, Snopes rated the claim false in January 2026, Reuters found no supporting evidence, and the Island Boys themselves denied ever meeting Epstein in a 2023 statement to TMZ.

Still, a bit of evidence (or lack thereof) should not spoil a good story. One user wrote:

“These scumbags ate children. Some documents state that they conducted rituals on a yacht and consumed the fetus; they even compared its taste to cheese. They are messengers of the devil in their purest form.”

Another claimed:

“Jeffrey Epstein emails with the gruesome subject ‘Slicing a Pizza’ probably means that Pizza-Gate is most certainly real. Sadly Conspiracy Confirmed.”

The Pizzagate theory — since widely debunked —was a conspiracy theory that exploded online during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, alleging that a child sex-trafficking ring involving prominent Democratic officials was being run out of a Washington pizzeria called Comet Ping Pong, interpreting food-related terms as code words. Posts suggested that words such as “pizza” or “steak” were code for children. One user alleged that an adoption charity founder asked Epstein if he needed “new steaks” for his island. A text search for the word “pizza” in the Justice Department documents comes up with an astonishing 849 results, most clearly related to Italian cuisine, but someone will no doubt find something there to reignite Pizzagate.

Others invoked comments made by comedian Roseanne Barr in 2024, when she claimed on a television appearance that Hollywood and political elites were “vampires” who drank blood and ate babies.

Note the antisemitic implications in the post above from someone who calls himself “ShavedWallaby”:

“Jeffrey Epstein and all his friends had code words for how they prepared the goyim babies and children to eat.”

“Goyim” is a word from Hebrew, found in the Bible where it means “nations”, particularly those being described in the narrative of wars from over 3,000 years ago: Hittites, Amorites, Jebusites, etc. Since then, its use has evolved to refer, sometimes disparagingly, to Gentiles, or everyone who is not Jewish. Most languages have a sometimes extensive range of words for outsiders; the Roma refer to outsiders as Gadjo, and the Japanese talk about foreigners as Gaijin. The person posting the above is implying that only non-Jewish children are being eaten at these dinner parties. Epstein of course is a Jewish name, although there is absolutely no indication that he adhered to any religious precepts whatsoever, and was certainly not a Zionist according to a tweet to Deepak Chopra revealed in the latest batch of documents from the Justice Department.

Other posters have alleged that they found evidence in the files proving Epstein was involved in “Baal worship”, was a “Mossad agent” or championed “Jewish supremacy,” old conspiracies are being repackaged as new revelations. In fact, the bank account named “Baal” was a scanning failure: the document says “Bank”. Also, for those who have ever looked at a Bible, a lot of it involves God telling the Israelites to avoid any contamination by the idolatrous Baal worshippers.

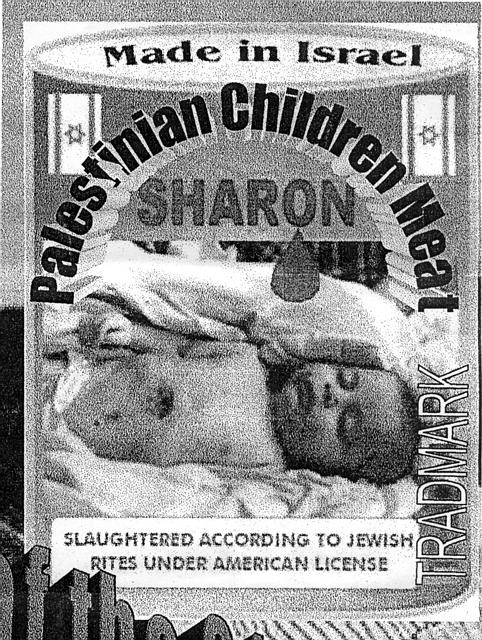

The reference to Jews eating (non-Jewish) children is, however, very familiar, even in the twenty-first century, and derives from the “blood libels” that caused riots and pogroms for centuries throughout Europe, starting in the twelfth century. Jews, and those accused of being witches, were tortured, exiled or slaughtered due to totally unsubstantiated claims of infant cannibalism, or more precisely the use of infant blood in religious rituals – an accusation that makes no sense when placed against the strict Kosher rules that forbid eating blood of any animal in any form. But such claims do not fade easily, and will often be seen in new forms, such as descriptions of Israeli soldiers deliberately starving, kidnapping or killing Gazan children in a (singularly unsuccessful) attempt to perform genocide. Only the most malicious and vituperative claims now involve cannibalism, and they are usually posted anonymously (I presume the above is a pseudonym since, in Australia, we do not usually shave wallabies).

A protest in Washington, D.C. on November 20 2025 featuring activists dressed as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, U.S. President Donald Trump, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and other officials dining on food and drink meant to resemble organs, skin and blood. The demonstration took place both inside and outside Union Station, the capital’s central train station. The activists deemed it as “Israel’s Friendsgiving Dinner,” with signage behind a long dining table displaying a menu consisting of “starter: Gaza children’s limbs,” “main: stolen organs,” “drink: Gaza’s spilled blood” and “dessert: illegally harvested skin.”

Meanwhile, this image appeared on the campus of San Francisco State University, or perhaps a modernised version of it (this one was from the second intifada). It is classic blood libel: Thomas of Monmouth would be jealous of the modern technology, but would recognise the vilification strategy.

Epstein’s crimes involved a type of cannibalism – the exploitation and abuse of children who were also supplied to other sexual predators. But despite the volume of accusations filling the social media of those with nothing better to do, there is no concrete evidence in the released documents that Epstein or anyone else in his circle of the rich, entitled and depraved engaged in actual consumption of babies. But then, I guess it’s a bit much to expect them to leave proof, or even bones, lying around. Men (and I guess a few women) who see themselves as gods, masters of the universe, happily guzzle all the evidence.