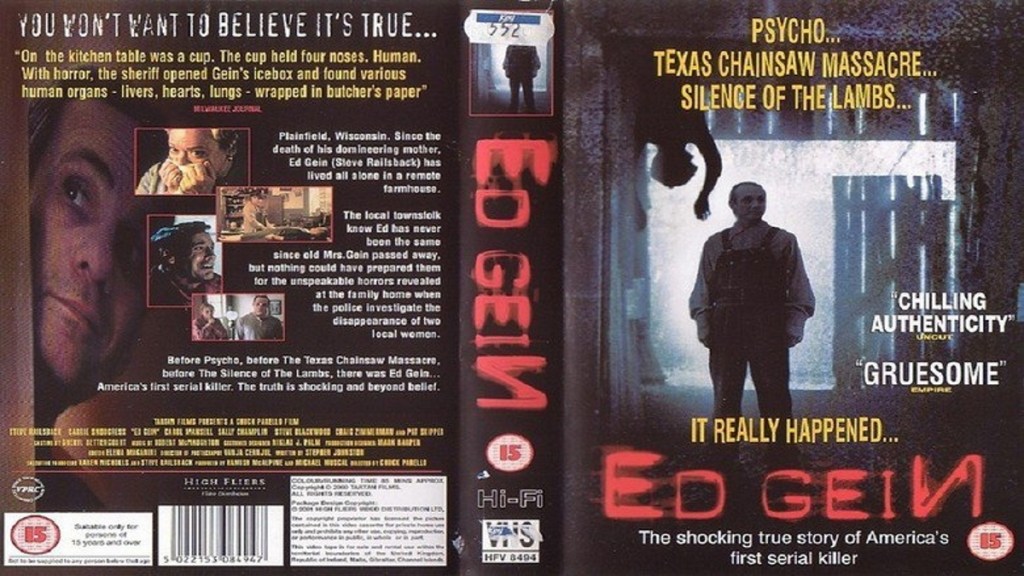

Long Pigs is a 2007 “found footage” movie, in which two desperate filmmakers come across a cannibal, ask him if they can document his eating habits, and then are shocked when he starts killing people and eating them. It is presented as a documentary, with all the usual warnings about graphic scenes etc.

Bit silly, and found footage has rather been done to death, but it has some interesting ideas, particularly the sympathetic approach to the main character, even as he commits his crimes. Look, it seems to say, everyone needs a hobby and, to this cannibal, killing and eating people is no more ethically questionable than hunting or fishing. Stalk, catch, kill (as quickly and painlessly as possible) and then enjoy. He does his best to keep the movie interesting, with a patter of jokes, historical facts and philosophical observations as he slices and dices.

The cannibal is played by Anthony Alviano (Headcase, A Matter of Justice), and he presents the cannibal, also called Anthony, as a boy-next-door persona, one who kills and guts people. Like a farmer of animals, he starts the film explaining that it’s bad to frighten the victims, not for ethical reasons, but because the adrenaline ruins the taste of the meat. The filming starts as he drives around looking for a “certain kind of woman”, because he wants to make “long pig stew”. “Long pig” is a term supposedly used in the Pacific region before colonisation to designate human meat, although that definition is widely contested. Anyway, Anthony is looking for “marbled meat”, so he searches for a sex worker (traditionally victims who are not exhaustively looked for by police) who is, let’s say, of a heavy build.

“People who eat stew make perfect stew. It sounds obvious. Yeah, she looks like she eats well.”

As she smiles at the camera, he sneaks up behind with a sledgehammer and cracks her skull, resulting in the cameraman vomiting (which is actually rather more gross than the murder). They ask Anthony if gets a sexual thrill from killing women, but he dismisses this, in the same way a slaughterhouse worker might deny any pleasure in killing a different species of mammal.

“I’m not a freak or anything like that. This is all culinary, this is hard work!”

“Any hunter would recognise this position. We got the corpse hanging by the ankles. The first thing I’m gonna do here is make a little incision and tie off the anus. That’s to stop contamination from the feces. You would do that whether it was a deer carcass or a cow or a person… Absolutely necessary for health reasons.”

He cooks a stew from a portion of her thigh, then after dinner goes off to brawl in an ice-hockey game, an arena that seems the very essence of carnivorous virility.

Afterwards, he cooks ribs on a barbecue, assuring the viewers that there are “no animal by-products” used – just soymilk. And a woman’s ribs, of course, thus reinforcing the anthropocentric mythology of the human as not really animal, even though he has just butchered one in the same way as any other animal prepared for human consumption. He quotes the Arawak word barbaca, the grill on which human meat was supposedly cooked, according to explorers like Hans Staden and Jean de Léry, which became the Spanish word barbacoa, and eventually morphed into English as barbecue. Staden’s narratives were later illustrated by Theodor de Bry in his 1592 book Americae Tertia Pars, and the film sneaks in a quick peek at that glimpse of sixteenth century sensationalism.

There’s a lot of moral philosophy interwoven in the scenes of murder and gastronomy. Anthony the cannibal and his friend try to persuade the filmmakers to try some of the ribs, saying, it’s dead, and therefore cannot suffer, whereas we eat live vegetables, and “broccoli feels pain! Did you know that?” This is precisely the argument tossed at vegans by carnists, but in this case, it demonstrates the contention of the nutritionist Herbert M. Shelton:

The cannibal goes out and hunts, pursues and kills another man and proceeds to cook and eat him precisely as he would any other game. There is not a single argument nor a single fact that can be offered in favor of flesh eating that cannot be offered with equal strength, in favor of cannibalism.

Anthony works as a valet in a fancy restaurant, parking cars for rude people, and if you follow the lore of Hannibal Lecter, you will know that rude people are prime targets of cannibals. They park the car of a particularly rude man, take down his address from his licence and, next day, shoot him and load him in their car trunk. Unfortunately, they have a flat tyre and have to head to a pig farm for help, where they witness pigs being slaughtered and prepared for sale, in identical ways to Anthony’s own processes, but with rather better technology, and, oh yes, totally legally.

Most of the film is a spoof on cooking shows, which regularly have smiling chefs, or hopeful chefs, preparing lumps of animal flesh, hoping to win prizes. Anthony shows, in high-speed motion accompanied by the music of the Sugarplum Fairy, exactly how he prepares a body, stripping it and dismembering it until all that is left is two feet (still in socks) and the long femurs. He demonstrates how to get rid of the bones, cutting them up and putting them in a kiln at 2600 degrees – he even uses the line “these are some we prepared earlier.” This is a cooking show for cannibals.

Anthony is a typical modern cognate cannibal; as he says, people expect Hannibal Lecter, so “no one is going to suspect the valet”. This gives him the invisibility that we saw in cases like Jeffrey Dahmer. He loves his old mother who is in a nursing home, and is bewildered by a doctor’s request to do a post mortem analysis brain when she dies, a sophisticated update of cannibalism. He sadly tells the filmmakers that she has Alzheimer’s, but we eventually find that she died of Creutzfeldt-Jakob spongiform encephalopathy, a human version of mad-cow disease, probably from eating human meat that he fed her. He also admits to eating a five-year-old girl called Ashley, because people prefer meat from young animals, but was subsequently perturbed by the extensive police searches, and now avoids playgrounds and schools: “It’s like a supermarket, man.” As New Year celebrations explode outside, he comes to realise the filmmakers are going to release the movie, which will detail all his criminal history, and goes to get his sledgehammer. The rest, as Shakespeare says, is silence.

Anthony has a philosophy that rejects anthropocentrism and sees nothing wrong with cannibalism, or at least nothing that does not apply to any other meat. It’s a cannibalistic rejection of what Richard Ryder and later Peter Singer called “speciesism”.

“It’s only human beings that are so arrogant that they believe they are better than every other kind of animal out there. Worms don’t think about, you know, oh my god, why did mama worm get eaten by a fish; fish eats the worm and that’s that, it’s completely accepted by the worm, and the fish, and small fish gets eaten by the big fish, and if it was so wrong to eat it, then why would it taste so good?”

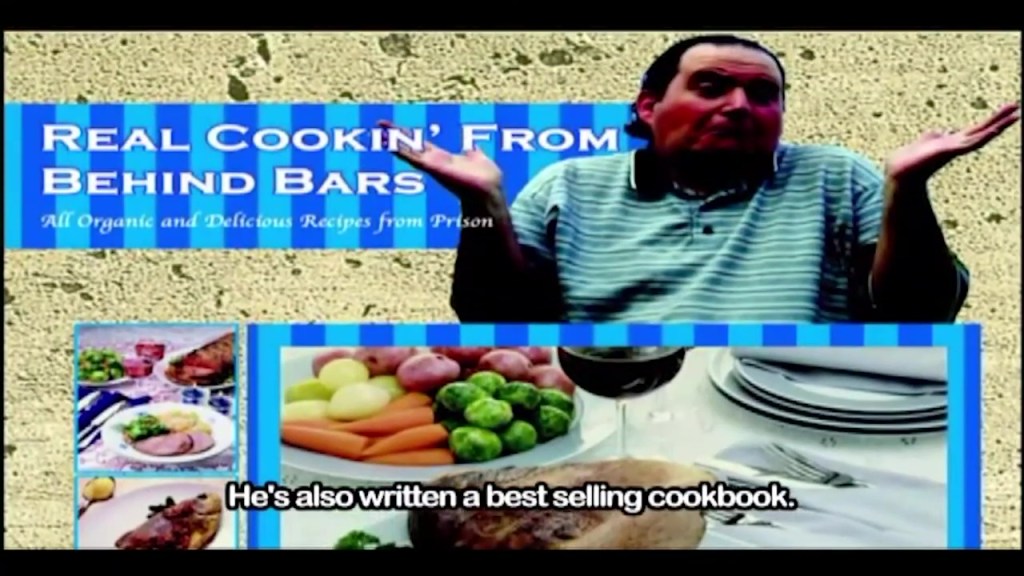

At the end, he is in jail, but he has published a cookbook. His cooking show has finally paid off.

This is a low-budget film, but is a lot better than might be expected. The creators were lucky enough to secure the services of Chris Bridges, the special effects artist whose credits include the Dawn of the Dead remake, Saw III & IV, 300 and Star Trek Discovery. Unless they actually killed and dismembered people, the result is spectacularly authentic. Anthony Alviano is brilliant in the role, which was written with him in mind.

The full movie (although slashed drastically from 81 minutes to 56 minutes) can, at the time of writing, be seen at https://youtube.com/watch?v=vnGXBRkxXuo.