This blog has laboured mightily to keep up with the constantly growing catalogue of cannibalism movies and TV shows, as well as the increasing number of actual cases reported in the media. So this week we are taking a rather exciting side-trip into the wonderful world of short stories, a place where the sets can be as lavish as the author wishes since there are no Producers cutting budgets, the protagonists can do anything the mind can conjure up without the need for stunt persons or insurance, and the whole thing requires no masks or social distancing.

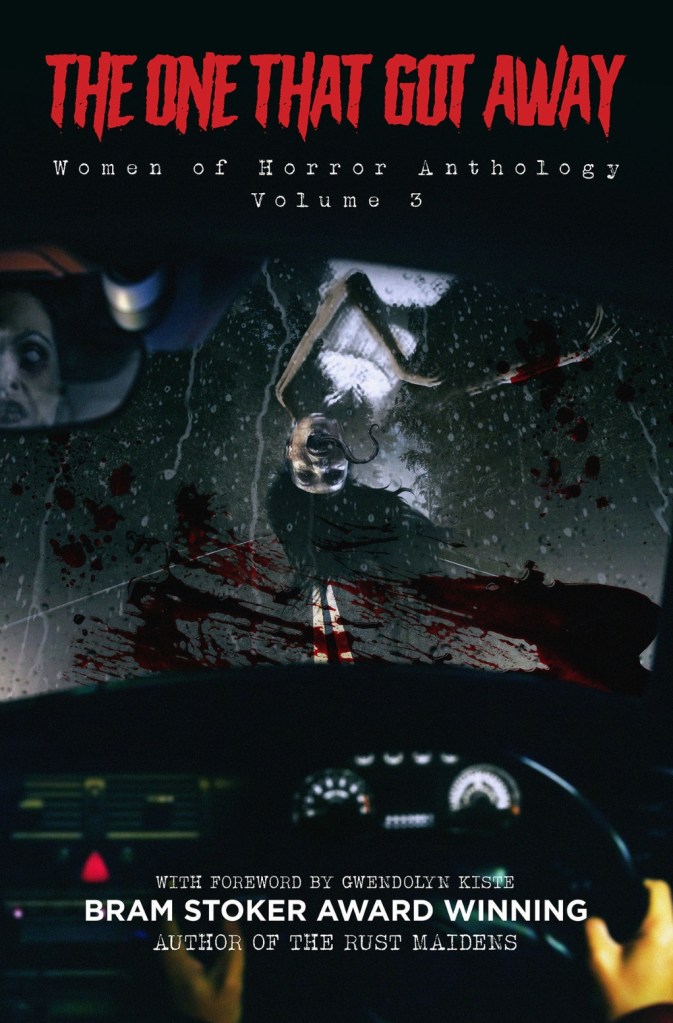

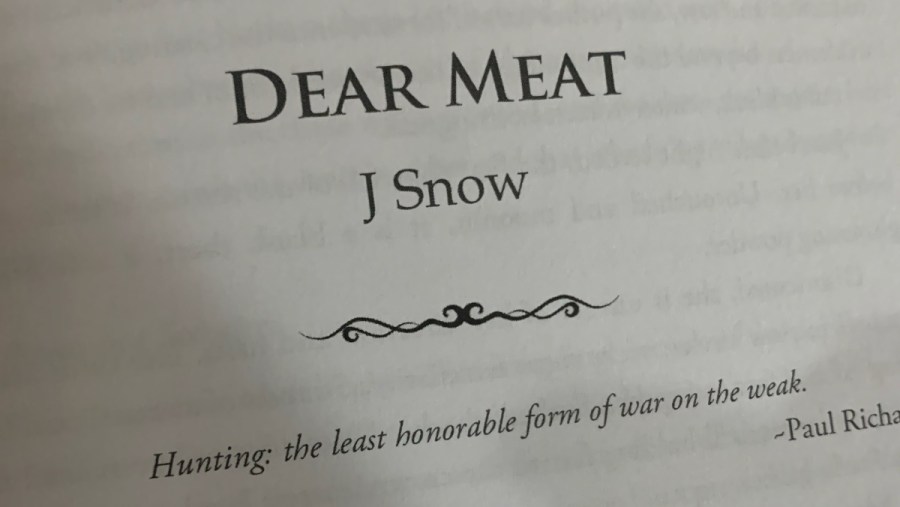

The story considered in this week’s cannibalism blog is called DEAR MEAT, and it appears in the third Women of Horror Anthology, titled THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY.

The anthology contains an amazing assortment of thirty fresh looks at the wonderful world of horror. I have, naturally, chosen to review the cannibalism story by J Snow, since that’s what I do, for reasons best known to myself and the Department of Culture and Communications at the University of Melbourne.

Ms Snow has written and published five cannibalism stories; reassuring to know that others also labour in these fields. For those of you who wish to know how (or why) she writes, there is an interview at Paula Readman’s Clubhouse.

Dear Meat was written a few years before the pandemic, but reads like it could be taken from tomorrow’s newsfeed. It involves a small elite group of rich and powerful men who have decided that human population growth is threatening to destroy the biosphere, and so must be stopped and reversed. More than two thirds of the population, billions of people, must be “eliminated.”

Various ingenious and possibly prophetic strategies are mentioned such as introducing viruses and tainted vaccines, genetically modified foods and contaminated water supplies. Free tubal ligations and vasectomies are encouraged, and abortions allowed up to two months after birth. But the key plan in this story is to set the populace at each other’s throats, or more precisely at the barrels of guns. Yes, hunting season for humans becomes the only way to feed the family. Tags are issued, which is apparently the way hunting works in the USA, and the distribution is weighted according to the discriminatory preferences of these shadowy rulers – the “unworthy and unholy” are allotted the most tags meaning the poor and the non-Christians are most likely to be hunted and cooked. Illegal immigrants are always open season. The rich and the politicians, however, don’t ever seem to end up on the butcher’s slabs.

English cleric and economist Thomas Malthus pointed out in 1798 that population increases geometrically, but food availability increases only arithmetically. All things being equal, this means we must run out of food, unless there is a disaster or an intentional reduction in human population growth. Too many people and not enough food is likely to lead to cannibalism, although Malthus did not venture into such abject speculations. The ethologist John Calhoun crossed that bridge in his study of rats, where he found that putting rats into a utopian environment, with no shortage of food or shelter, and letting them breed unconstrained, ended up in a chaotic maelstrom of sexual deviance and cannibalism. A Malthusian/Calhounian scenario is the basis for the film Soylent Green which is set (honest, I’m not making this up) in 2022, when overpopulation has led to a situation where the enormous population of poor people can only be fed by recycling the bodies of those who die or can be persuaded to accept euthanasia.

Not so in Dear Meat. The people running the government know one thing that has been true since the start of humanity: when there is hunger,

“People turn on each other, become monsters, all for one tiny morsel.”

The people turning on each other in this story are from a family; a man, a woman and a child. Not even close to a large family by today’s standards, but in the world of the story, any increase in population (child) must be balanced by a decrease (a hunted tag). One person must die, be carted to the butcher and carried home as meat, just as the odd hunter does now to deer or kangaroos or anyone else that happens to move at the wrong moment.

I am introducing some levity because this is a grim scenario, skilfully crafted, beautifully written and with an ending that I absolutely will not spoil. The wonderful thing about eBooks is that they are ridiculously affordable and offer hours of reading pleasure. This collection, and particularly Dear Meat, is highly recommended.

Here’s a review from Goodreads:

And here’s one from Amazon:

The author’s details are here, and the book is available at on line retailers including Amazon.