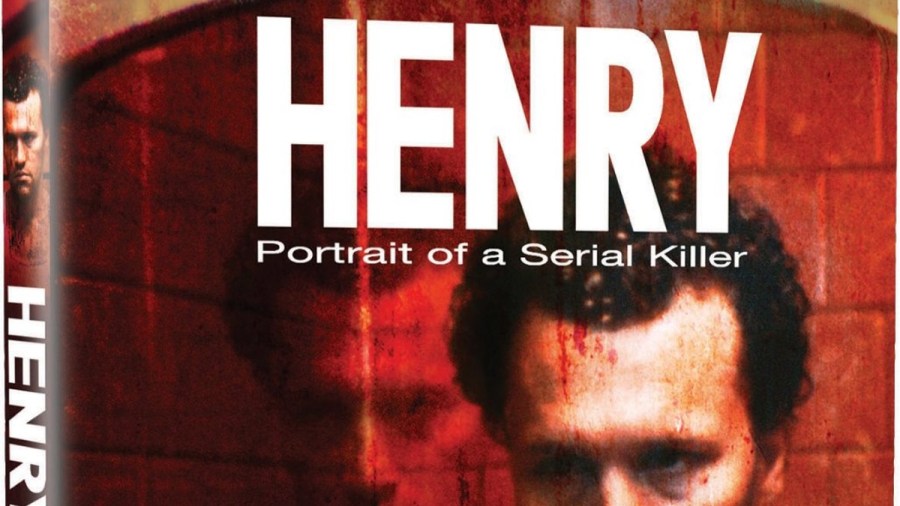

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is an American psychological crime film directed and co-written by John McNaughton that depicts a random crime spree by Henry and his protégé Otis, who torture and kill with impunity. Michael Rooker in his debut film plays the nomadic killer Henry, Tom Towles plays Otis, a prison ‘friend’ who lives with Henry, and Tracy Arnold is Becky, Otis’s sister.

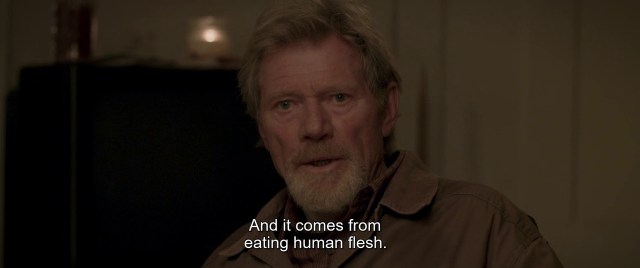

The characters of Henry and Otis are loosely based on convicted real life serial killers Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, who was famous for his claims to have cannibalised many of their victims, claiming that they also supplied women and children for human sacrifice to a cult called “The Hand of Death”.

Henry confessed to over 600 murders, which supposedly were committed between his release from prison in 1975 to his arrest in 1983, a pace that would have required a murder every week. A detailed investigation by the Texas attorney general’s office ruled out Lucas as a suspect in most of his confessions by comparing his known whereabouts to the dates of the murders to which he had confessed. It appears that the police would bring any cold case to his attention, feed him information about it, and then let him take responsibility. He had nothing to lose, and global fame and notoriety to gain. He was convicted of 11 murders and sentenced to death for the murder of an unidentified female victim known only as “Orange Socks.” His death sentence was commuted to life in prison by Texas Governor George W. Bush in 1998 due to evidence that Lucas was in Florida at the time “Orange Socks” was killed in Texas. Lucas later recanted all his confessions except for the murder of his mother, and died in prison of heart failure on March 13, 2001.

The film involves a lot of scenes of Henry driving his battered old Chevy Impala around the grey streets of Chicago, finding people to kill. Images of bloody mayhem are offered for their shock value and become repetitive, and rather fake, but then the film was made on a tiny budget.

Some narratives in the film run parallel to what we know of the real serial killers. Henry did meet Ottis, but in a soup kitchen in Jacksonville, Florida, not in prison. Henry’s father really did lose both of his legs after being struck by a freight train, leaving Henry at his mother’s mercy. But the film largely omits the long-term homosexual relationship between them (shyly hinting at it when they share the last can of beer) and, sadly, totally omits Ottis’ predilection for cannibalism.

Henry did sexually abuse Ottis’ 12-year-old niece Frieda Powell, who lived with them for many years. As in the film, Powell preferred to be addressed as Becky rather than Frieda. However, in the film Becky is Otis’s younger sister, and is presented as a considerably older single mother, not the real 12-year-old Powell.

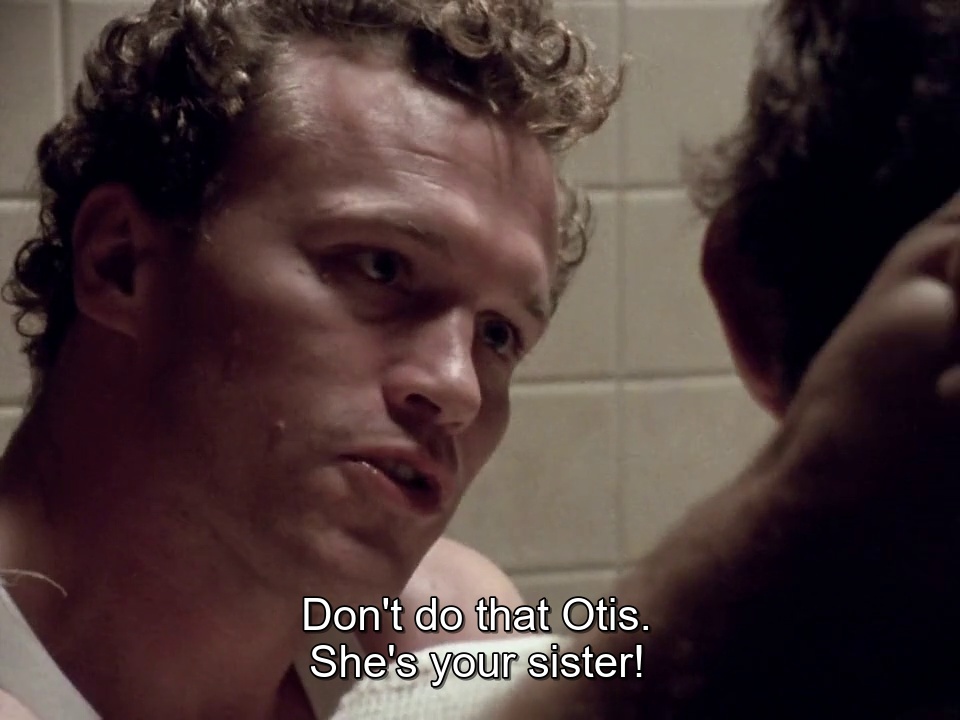

Sexual neurosis is presented as the root cause of the violent tendencies of both men. Otis, who is shown attempting to sexually abuse his sister, tells her that Henry killed his own mother, and when Becky asks Henry about it, he tells her his mother was a sadist and a “whore”, who forced him to watch her having sex with clients, sometimes making him wear girls’ clothing for further humiliation.

Becky in response tells Henry of her childhood, in which she was regularly raped by her father, with her mother claiming not to believe her.

“He told me he had a right, because he was my daddy and I was his daughter, and he fed me and let me live in his house, and he could do whatever he wanted. And he did… I didn’t fight him, because when I did he just hit me.”

Henry introduces Otis to his world of serial killing when they pick up two sex workers and Henry snaps their necks during sex, suggesting that he is revenging his mother’s abuse. To Henry, the world is against him, and murder is “always the same, and it’s always different.”

Otis gets a taste for murder when they kill a fence who mocks them when they try to buy a television from him, and then actively seeks out opportunities when a high school boy he comes on to punches him in the mouth. Henry says it would be a mistake to kill the boy, since they’ve been seen together, but Henry wants to kill someone. It’s the world being against them, again.

Henry schools Otis to make sure every murder is different – that way there can be no M.O. for the police to follow. A particularly brutal scene of the murder of a family is videotaped by the pair (on a camera stolen from the dead fence) and Otis enjoys re-watching himself molesting the screaming woman, breaking her neck and then attempting necrophilia, until Henry orders him to stop, just as he forced him to desist from molesting Becky when she arrived. When Henry finds Otis raping his own sister, he fights him and with Becky’s help, kills him.

Henry has his own moral code, in which murder is fine, but incest, family violence and necrophilia are forbidden. The real Henry’s paedophilic involvement with twelve-year-old Becky, and the real Ottis’ interest in eating people, are never mentioned.

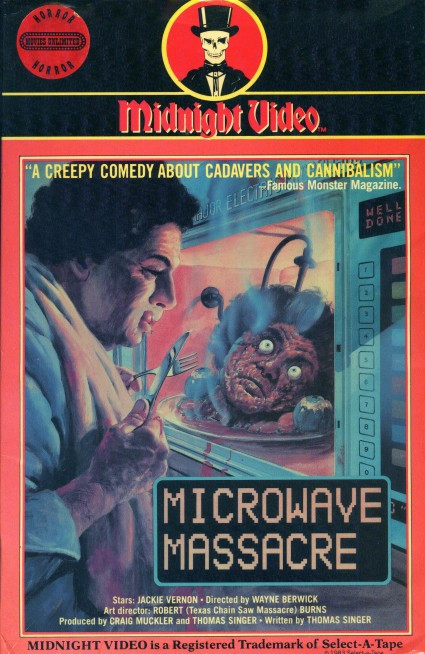

Incest, murder and cannibalism are the three great taboos of our civilisation according to Freud, the driving forces behind the creation of laws and morals, which stop us destroying our communities by doing those things. The movie sadly concentrates on the murders and has references to incest, but totally ignores the cannibalism.

Unlike the film, the real Henry did not kill Ottis – both men died in separate prisons, Ottis in Florida State Prison in 1996 and Henry in Ellis Unit, Huntsville, Texas in 2001.

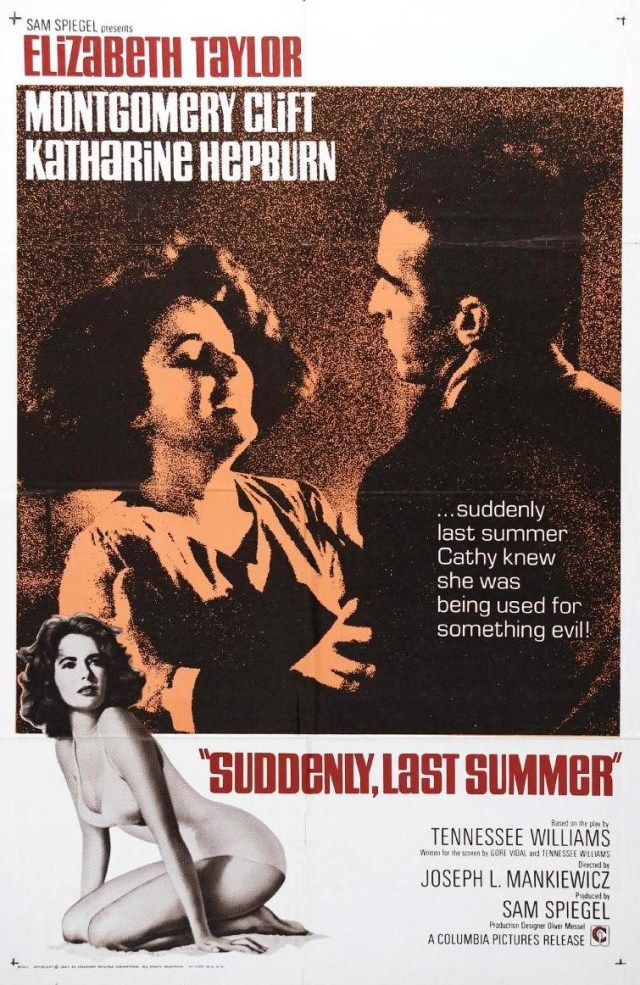

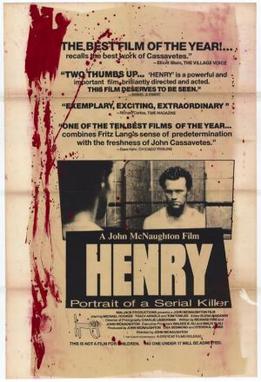

Due to the violent imagery, the film was censored in many markets and the original poster (above) was banned. The controversy brought it some very valuable publicity. The reviews were also mostly positive – it has an 89% “Fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with Roger Ebert observing that the film does not “sugar-coat” or trivialise violence as most slashers tend to do, and calling it:

“a very good film, a low-budget tour de force that provides an unforgettable portrait of the pathology of a man for whom killing is not a crime but simply a way of passing time and relieving boredom.”

It’s well made (considering the miniscule budget), the cast are terrific (in both senses of the word) and the plot, if somewhat out of step with the reality of the case, is well presented and never dull. But why should it stick to the “facts” of the case, when clearly neither Henry nor Ottis were too sure what was real and what simply bravado?

A sequel, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer Part II, was released in 1996, but without any of the cast or crew from the original.