Wendigo is a film written, directed and edited by Larry Fessenden, who would, a few years later, make an episode of the TV horror series Fear Itself called SKIN AND BONES, which was about a guy who disappears on a hunting trip with friends and returns cold, thin and desperately hungry. He has, we quickly discover, become a Wendigo! In this, the earlier film, there are also crazy hunters led by Otis (John Speredakos), who are mad with our protagonists for driving into a stag (the traditional symbol of the Wendigo) who they have been tracking and, worst of all, breaking his antlers, which are apparently very valuable. The Wendigo is already there in their cabin as a “dark presence”, so we just need to be introduced.

First, the really good cast – George (the Dad) is played by Jake Weber, from the 2004 remake of Dawn of the Dead and Meet Joe Black. He is a super-stressed New York photographer, and the last thing he needs is a run-in with a bunch of redneck hunters. Kim, the Mom, is played by the wonderful Patricia Clarkson (most recently starring in Gray) and the kid, Miles, is played by Erik Per Sullivan, who was Dewey in Malcolm in the Middle.

George is more disturbed by the rednecks than he is willing to let on, telling Kim, who is a psychologist, that he is distressed by the “abyss” between him and them, with no possibility of communication. She tells him that:

“It’s very archetypical for the civilised man to feel threatened by the man of the country.”

George is utterly divorced from nature, seeing it as alien and menacing. So, the other last thing he needs to meet is a Wendigo, a figure on the front line of the human war on nature.

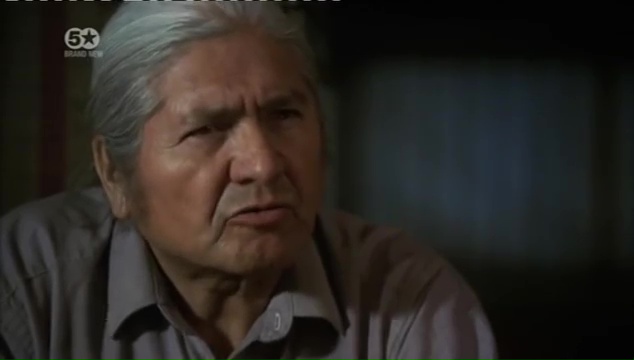

They head into town to buy curry (as you do in small towns) and Miles meets in the store a Native American Elder who tells him about the Wendigo, a small carving of which Miles is drawn to.

“The Wendigo is a mighty powerful spirit… it can take on many forms, part wind, part tree, part man, part beast. Shape shifting between them… It can fly at you, like a sudden storm, without warning, and consume you with its ferocious appetite. The Wendigo is hungry, always hungry. The more it eats, the bigger it gets, and the bigger it gets, the hungrier it gets, and we are hopeless in the face of it. We are consumed, devoured…. There are spirits that are angry. Nobody believes in spirits anymore. Doesn’t mean they’re not there.”

The Wendigo is a figure from the mythology of the Algonquin people of North America. They lived in a land of long winters where the competition for food would have been intense and cannibalism of the dead probably not unusual. Myths help to spell out behaviours that societies need to discourage – cannibalism could decimate small, isolated communities. That myth, of the voracious monster whose hunger only grows with feeding, was later applied to the invaders, the colonists who took their land, their produce and often their lives. In such a struggle, the Wendigo, as an original figure of their culture, could take almost a vengeful role, eating the technologically superior invaders. George inadvertently confirms this, telling Miles “the Wendigo only goes after bad guys.”

The Elder tells Miles he can keep the figure, but there is no sign of him when Kim is subsequently asked to pay for it. He is presumably one of those spirits, not angry but advisory. He warns Miles about the “cry of the Wendigo”. The Wendigo is clearly (to the audience) imbued into that carving.

Then the Wendigo strikes. Or is it the rednecks? Did the Wendigo knock George off his sled, or did it carry him home after Otis shot him? Was it the revenge of nature, or society? When the Wendigo later demands of Otis “Give me my liver!” it voices the cry of revenge of every animal, human and otherwise, killed for fun or profit. When Otis meets justice, Miles awakes with his Wendigo figure in his hand.

It’s a great cast, with an absorbing plot, although it gets a bit lost at the end. But the questions it asks are compelling. The New York Times critic wrote:

“Mr. Fessenden carefully blurs the line between psychology and the supernatural, suggesting that each is strongly implicated in the other. The rampaging Wendigo may be a manifestation of Miles’s incipient Oedipal rage, but at the same time it is a force embedded in nature and history.”

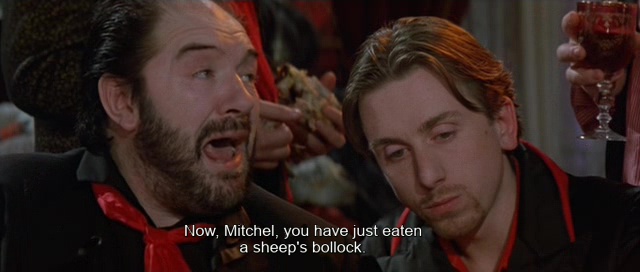

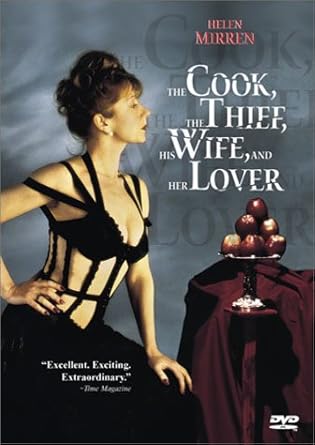

The Wendigo carries so much symbolism, besides the horror trope in which he seems so regularly to find himself, such as in Fear Itself or the classic Wendigo film, Ravenous, which was made a couple of years before this film. He expresses the anger that rages within George, the father who cannot show interest in his son’s curiosity because of his own issues brought with him from the city, frustration and fear of failure. And we can infer (as the NYT does) that Miles himself feels an Oedipal rage toward his father who, Freud tells us, is the child’s rival for sexual possession of the mother throughout childhood. The voracious hunger comes from an even earlier stage, what Freud called the “cannibalistic stage” of babyhood, where the infant wants to own the breast, consume it so it will always remain in his possession. George’s playacting the cannibal, attacking and pretending to eat Miles, is a common parent/child game, but is also deeply revealing of these forces hidden deep in the unconscious.

At yet another level, the Wendigo represents the revenge of nature on the civilised, those whose insatiable hunger for growth decimates the land and finds sport in killing its inhabitants, be they human, deer or any ‘other’. The antler is a weapon used by the stag, a normally shy and timorous animal who becomes a formidable fighter in the mating season, and the size and strength of its antlers represents both its sexual and fighting prowess. In the hybrid shape of a human and a stag, the Wendigo recasts humans from hunters to hunted, from predator to prey. This is precisely why Hannibal Lecter is shown in Wendigo form throughout much of the three seasons of the television series Hannibal. Hannibal is the civilised, rational, erudite man of science, a psychiatrist who knows of the dark forces inside the human psyche, and has determined that the human is just another animal, no more deserving of respect or inedibility than any other species, and even less if he happens to be rude. Who judges that – the supernatural force, the inhuman, the less-than-human or, in Hannibal’s opinion, the more-than-human? Whichever you choose, it appears as the Wendigo.