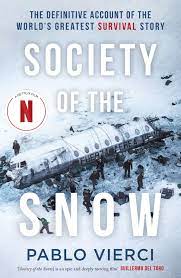

Society of the Snow is a new account of the 1972 Andes plane crash. It is an adaptation of Pablo Vierci‘s book of the same name,which included detailed accounts of all sixteen survivors, many of whom Vierci had known from his earliest years.

The twist here (not really a spoiler as they keep presaging it) is that the narrator of the film is one of those who were not among the sixteen.

Uruguayan Air Force flight 571, chartered to transport the “Old Christians” rugby team to Santiago, Chile, crashed into a glacier in the heart of the Andes. Of the 45 passengers on board, only 16 survived for the 72 days before they were rescued. Trapped in one of the most inaccessible and hostile environments on the planet, they had to choose cannibalism to stay alive. In this blog, we are most interested in the debate that led to the decision to eat their friends and crew, but the whole story of their pursuit of survival goes beyond what they ate and is equally fascinating.

We see a group of very devout young people, laughing and joking as they organise the trip to Chile, horsing around as the plane gets most of the way over the Andes, and then their reactions as the plane just does not reach the required altitude.

After a week without food, their urine turning black from lack of protein, they start exploring their very limited options. One group believe they will be rescued, even though their plane is painted white and they are in one of the biggest snowfields in the world. But most of them start to think about the only realistic way to survive, particularly after they find a portable radio and hear that the search for them has been called off.

The film has some interesting discussions regarding the ethics of cannibalism.

“What’ll happen to us? Will God forgive us?”

“He’ll understand we’re doing everything we can to survive.”

Roberto, the medical student who has been trying to keep the injured alive, explains what happens to the body without food – it dries up, starts to absorb the organs. There is reference to the “God of the Mountains”, a different being to the one in the city. Arturo, one of the wounded, has a fascinating soliloquy about this God:

“That God tells me what to do back home, but not what to do out here…. I believe in another God. In the God that Roberto has in his head when he treats my wounds. In the God that Nando has in his legs when he keeps walking no matter what. I believe in Daniel’s hands when he cuts the meat, and Fito when he gives it to us, without saying which of our friends it belonged to. So we can eat it, without having to remember the life in their eyes.”

They discuss the legality and the practicality of cutting up bodies, the similarity to organ donation, but of course without consent. So that inspires them to make a pledge.

And so they begin to eat. There are scenes of skeletons being picked clean as the three Strauch cousins offer to cut up the bodies in an area that is hidden from the plane, “to keep the ones who eat from losing their minds”.

What the film glosses over is the Catholicism that permeates much of Latino culture. While they make the point that the bodies are now “just meat”, they do not look for the parallels of their cannibalism to the Eucharist, the eating and drinking of the wafer and wine in church which is supposed to transubstantiate into the blood and body of Christ. It is a theme explored in more detail in the earlier film, as well as in the memoirs of the survivors.

“Drawing life from the bodies of their dead friends was like drawing spiritual strength from the body of Christ when they took Communion”

(Parrado & Rause 2006. Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home, p.117.)

They quote to each other Matthew 26:26: “Take and eat, this is my body.”

(Canessa & Vierci 2016. I Had to Survive: How a Plane Crash In The Andes Inspired My Calling to Save Lives, p.27).

I suspect this might have been considered a bit too close to the bone (apologies for the pun) for the Spanish speaking audience to whom the film is mainly addressed. Or else they wanted to appeal to a wider audience than just the Catholics. Or perhaps a bit of both.

The story is best known in print for Piers Paul Read’s 1974 book Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors, which was turned into the film Alive in 1993 by Frank Marshall. Since then, several of the survivors have written their own accounts, to set straight some of the alleged inaccuracies in Alive, but none are as well known. Outside of the Hannibal story and perhaps Soylent Green, Alive is the film most people seem to recall when they hear I have written a thesis on cannibalism.

Alive had a few problems that this film nicely avoids. For one thing, it was very Hollywood, or “Anglo” as the politically aware like to say. It starred American actors who did not look like they were starving, even when they were fondly reminiscing and lusting for the food they missed, which seemed to be mainly pizza. Society of the Snow has Uruguayan and Argentinean actors speaking in Spanish, and makeup and special effects have improved markedly in the thirty years between the films, so they look hungry, and their wounds look ghastly. It is a more authentic look at the situation in which a group of deeply religious young men could decide to eat their dead fellow passengers and friends, who conveniently lay around them, preserved in the snow.

The film closed the 80th Venice International Film Festival in an ‘Out of Competition’ slot. It was theatrically released in Uruguay on 13 December 2023, in Spain on 15 December 2023, and in the US on 22 December 2023, before streaming on Netflix in January 2024.

Society of the Snow received positive reviews. At the 96th Academy Awards, it was nominated for the Best International Feature Film, representing Spain, and Best Makeup and Hairstyling.

Society of the Snow is arguably a better movie than Alive, although at two hours forty minutes, I thought a bit more editing might have been useful. Still, sitting through that 160 minutes gave a miniscule sense of the despair of sitting in a wrecked plane in freezing conditions for 72 days, so we cannot complain!

But I was sorry to see them drop the cannibalism/communion issue, even though there is a hint in the final scene where the survivors sit around a dinner table like the Disciples at the Last Supper, their dead friends being the bread of life, transubstantiated from sacred to edible, the reverse of what is supposed to happen to the church wafer. Whether you consider this a cannibal movie or an epic of survival (and yes, there is controversy raging about that), exploring why people do or don’t eat each other is endless fascinating, and the question of cannibalising the body of Christ is, or should be, at the heart of this story.