Pluribus (or in the titles “Plur1bus”) is the latest series from Vince Gilligan, the genius behind Breaking Bad and its sequel, Better Call Saul, as well as some thirty episodes of X-Files and its spin-off, The Lone Gunmen. I watched Breaking Bad and BCS compulsively (even though there was no cannibalism in them) because they forensically unwrapped the thin veneer of civilisation that tries to conceal the greed and violence underlying human societies.

Pluribus goes to the next step, exploring the nature of solutions that have historically been offered to the depraved appetites that motivate and terrify us – food, territory, sex. It envisages a utopia that is an allegory of every kind of perfectible society attempted from religion to revolution, all of which start by wanting to save us all from war, violence, oppression and hatred, and end up enforcing their perfect society with brutality, bloodshed and the suppression of individual liberties and thoughts.

In this scenario, Carol Sturka (Rhea Seehorn from Better Call Saul) finds that virtually everyone else on earth except a handful of immune people have been affected by a virus whose origin is a stream of data from a distant galaxy. They have merged their minds into a collective consciousness, a “hive mind”. Imagine if suddenly everyone around you was inhabited by ChatGPT and had all the knowledge of humanity at their fingertips, was polite and helpful, and wanted you to join them. Or if not AI, then consider meeting members of a cult. They are always so polite – until perhaps you join them! No one is an individual any more – the “joining” has caused almost everyone to share their thoughts, their knowledge, their talents.

Violence is therefore totally obsolete, unimaginable, the way that murder was considered unthinkable in the “workers’ paradise” of the Soviet Union. It is the ultimate form of Communism, where everyone works together for the common good like bees or ants, there is no dissension, and no one is exploited or killed (except when Carol has her tantrums). Carol is the outsider, the one who does not fit with the smothering conformity that society calls well-balanced happiness. Imagine a vegan in a Beef Week parade. She has, by a freak of genetics, taken what The Matrix calls the red pill – the one that sees even painful individuality as more important than submission to comfortable conformity. So, when Carol expresses her rage, thousands of people die from the shock waves of her uncontrolled emotions. In fact, the show’s log-line is:

“The most miserable person on Earth must save the world from happiness”

That’s the background, and if you haven’t watched it yet, you may wish to stop reading here and go turn on Apple TV, who outbid Netflix for it. Because there is a big spoiler – for the viewer, and for Carol, who by almost the end of the season has found love with one of the hive people (who of course is also everyone else on earth) and comfort in the fact that she herself is immune and cannot be ‘saved’ without giving them, voluntarily, her DNA from stem cells.

This is a blog about cannibalism, so let’s look more closely at what all humans, even perfectly happy, hive mind ones, have to do: eat. Pluribus is, in a way, a reboot of Robinson Crusoe, sometimes sited as the first English language novel. Like Carol, Crusoe is alone, either psychically in her genetically forced separation from the hive mind, or literally when she causes such havoc that the others all move out of town (it’s set in Albuquerque like earlier Gilligan shows), leaving her isolated, forced to entertain herself with fireworks and golf. But Crusoe discovers that there are other humans visiting his island – cannibals who capture and kill rivals for dinner.

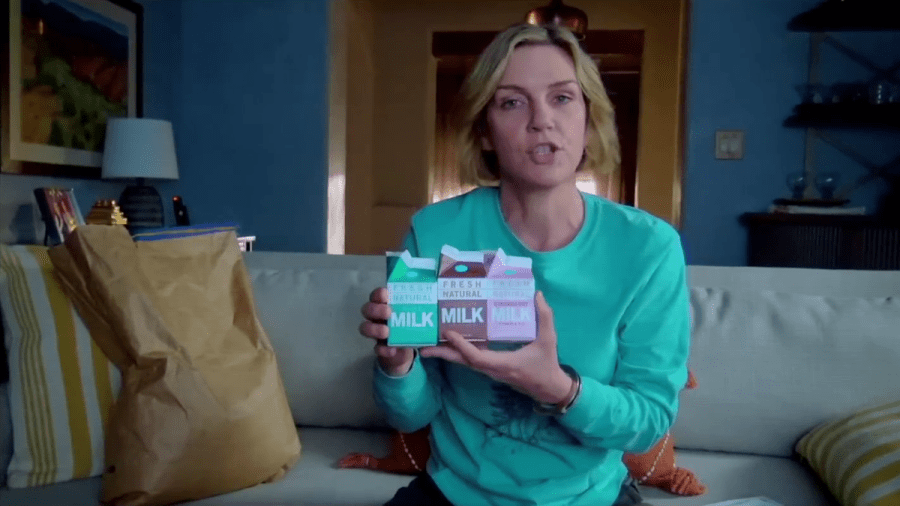

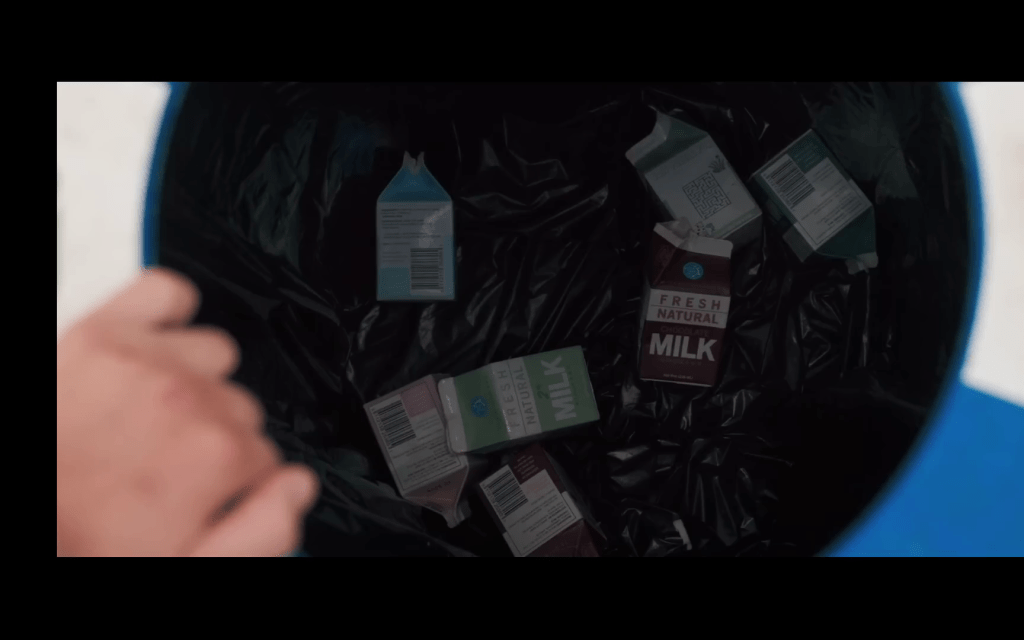

Carol similarly discovers cannibalism. Dumping her trash, she finds a large number of empty milk cartons in one of the town’s rubbish bins from a local dairy. She observes in episode 5, “Got milk”:

They sure like their milk”

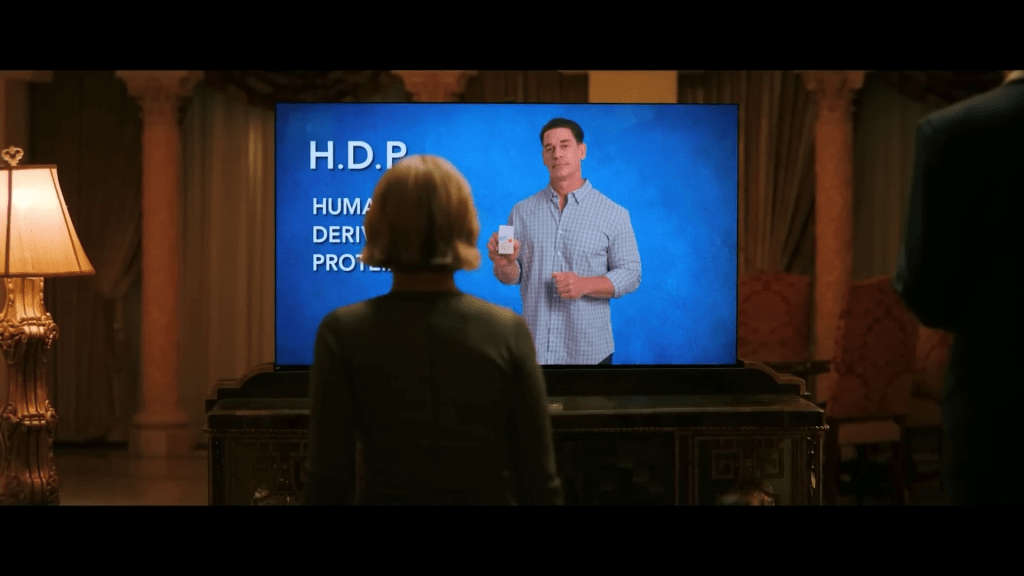

She investigates and finds that, instead of milk, the dairy is producing a strange fluid created from a bagged crystalline substance. In episode 6, “HDP”, Carol traces the origin of this substance to a food packaging plant.

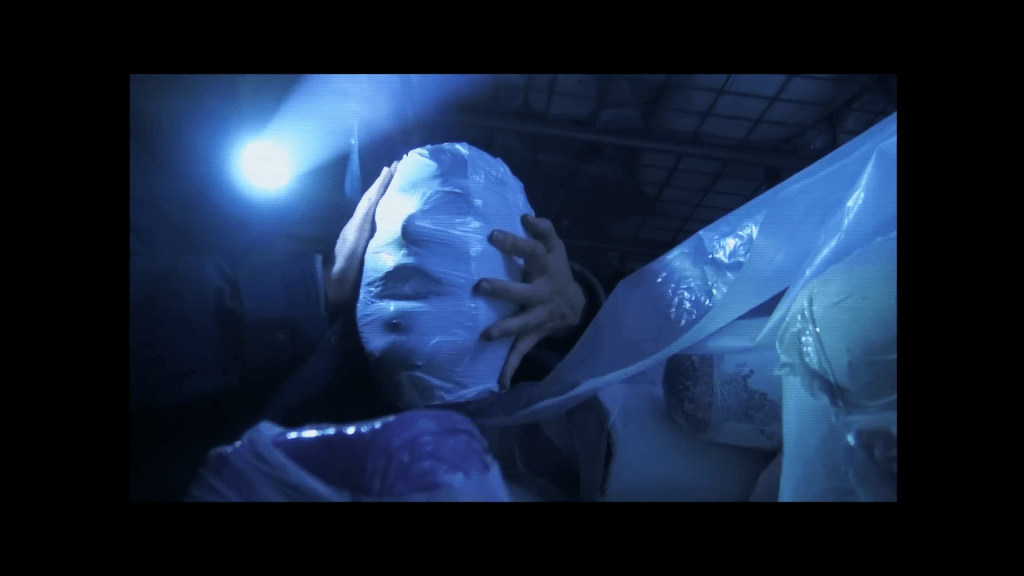

At this point, if you are a regular reader of this blog, you will have come to suspect the origin of this mysterious substance. Yep, like Soylent Green, the answer to starvation caused by overpopulation is simple – process and eat the dead humans. “HDP” stands for “Human Derived Protein”, and the plant is full of snap-frozen human body parts, presumably some of the millions of people who died during the joining. She picks up a frozen human head which (fun fact) is Vince Gilligan’s.

Like the plane crash survivors in Alive, there is nothing else for them to eat. A member of the others, played by John Cena (actor, wrestler, rapper and Peacemaker), explains that consuming people is not the Joining’s preference, but is instead a last resort to avoid mass starvation as their strict non-violence has extended to all other life, animal and plant; they have freed the animals from farms and zoos, and will not even pick an apple unless it falls from a tree by itself.

Carol’s hope that this discovery will unite the dozen immune non-joiners in her crusade to undo the joining proves in vain – they don’t care, just like the on-lookers didn’t really care that “Soylent Green is people!” as Charlton Heston screamed as he was being carried out. They don’t even let her join their video conferences due to her propensity to rage.

The joined, represented by Cena, are open and honest about their solution to starvation. The world has become a perfect utopia, except that there is nothing to eat except the waste product of the joining: human corpses. They explain to Carol that nearly 100,000 people die every day on Earth from natural causes. The Others are recycling those bodies like industrial food waste.

They call it “honouring the memory of the deceased.” As Alive asked, isn’t cannibalism better than dying of starvation? And, the next logical step taken in this show, isn’t it better to eat the dead than the living?

Carol by now has been abandoned by the “others”, even though they deliver to her anything she requests, usually by drone. Driven to distraction by isolation, she asks them to return, but writes a reminder to herself on her whiteboard, underlining it aggressively:

“THEY. EAT. PEOPLE”

The reminder stays there on her whiteboard, but she is so traumatised by isolation that she accepts their help and the love of the woman sent to contact her, even though she understands that she is just one cell in the hive mind. She also knows that the situation is unsustainable and that the others will soon be dying of starvation by the millions when they run out of corpses. But what finally changes her mind, makes her back into the outsider, is that she finds that the others have worked out how to develop new strains of the virus specifically for the immune. They already have her DNA from her eggs which she froze earlier in her life. They are planning to get her to join them.

Carol puts in a special request: an atomic weapon. She is determined to return humanity to its old individualistic self: fighting, raping, and exploiting each other, and, like John Cena’s Peacemaker, seems to be willing to kill them all to get there.

So the joining, like all utopias, turns out to be a nightmare from which millions will wake up dead. Although Carol has rejected the idea of joining, she has accepted that the rest of humanity is already joined and she is the glorious outsider, the non-conformist. What changes her mind is the realisation that they will not rest until she joins them too, despite the dire outlook for continued human existence.

What about the “milk” – the HDP? She is shocked when she finds the freezers full of human body parts, horrified to hear that this is what they eat to supplement the fast-dwindling supplies of food from before the joining, but, as they explain to her, the HDP is from people who have already died – there is no violence involved. Unlike our societies where billions of innocent and gentle animals are kept in appalling conditions and slaughtered industrially, the others have created a society along the line of what John Lennon hoped to see:

“Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people

Living life in peace”

She just doesn’t want to join them and, you know, EAT. PEOPLE.