There are tendencies, dispositions, that characterise each era, each year, sometimes each day. Call them spiritus mundi or the zeitgeist, they appear to us in the media of the time – never more so than now, when we can express instant expression and instant outrage on social media. The current trend seems to be about oppressive elites who are manipulating, enslaving, sometimes consuming us. On the ‘right’ this is sometimes expressed as “the Deep State”, on the ‘left’ it is variously called capitalist exploitation or racist colonialism.

A story that has been doing the rounds for a decade has recently gone (a bit) viral again this month after a podcast called Mexico Unexplained revisited the story of Gabriela Rico Jiménez, a 21-year-old model from Mexico who disappeared some 15 years ago after raging against the machine outside a fancy hotel in Monterrey Nuevo Leon. Jiménez is usually described as a “supermodel” although there is little evidence of that in Google searches. But then again, if she has been “disappeared” by the elites against whom she railed, then they would have made sure to delete her history as well, n’est pas? The Daily Mail rediscovered the story on June 1 2024 and brought it back to life:

Anyhow, she made some interesting if somewhat mystifying accusations:

“I wanted my freedom. Monterrey freed me but it cost me a lot of work. I was in Mexico City for a year and four months. All this began in mid-2001. I barely remember. They were young and powerful, and they killed them. I’ve been knocking on doors. What I wanted was my freedom. I want my freedom. Carlos Slim knew about this. I want my freedom. It hurts my soul that they took him away.”

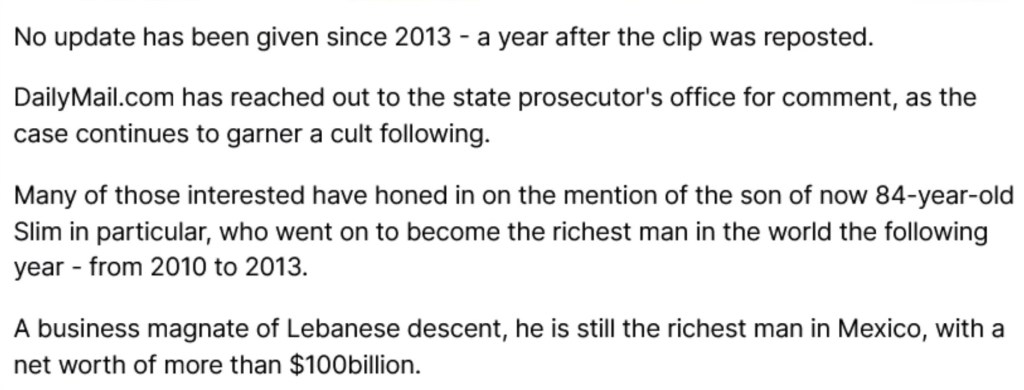

Carlos Slim at that time was apparently the richest man in Mexico or maybe the world, controlling América Móvil, Latin America’s biggest mobile telecom firm, so it’s not too surprising that her rant was shut down pretty quick, and she was carted off, presumably to a mental asylum, wherein she perhaps still rots, unless she has been cured, killed, or eaten.

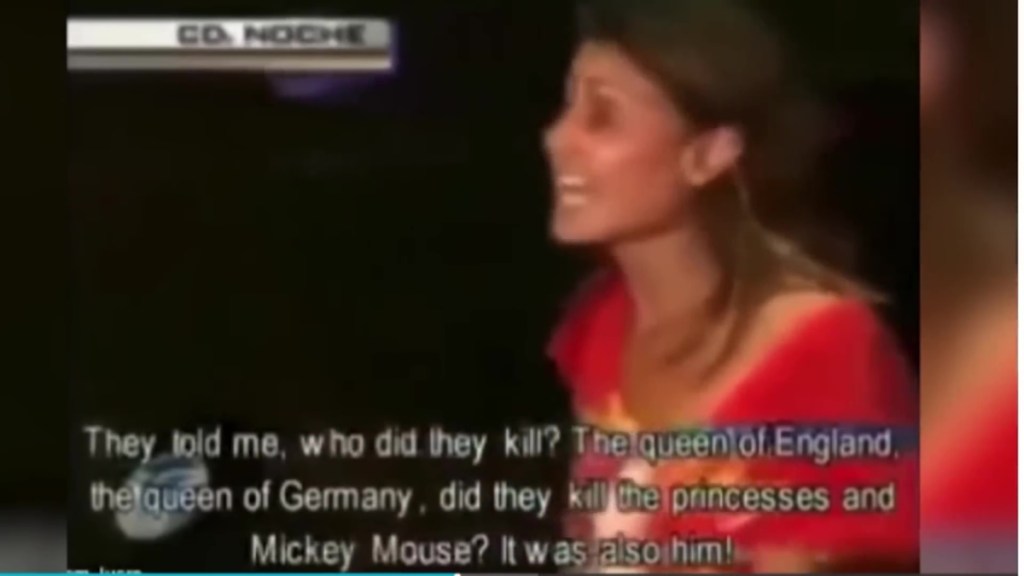

As the police (or stooges of the elites if you prefer) began to move in, she screamed,

“You! You were there! … You killed Mouriño! They told me who did they kill? The Queen of England? The Queen of Germany? Did they kill the princesses and Mickey Mouse? It was also him! What? Nothing is going to come here. The people where you come from are crazy! They killed a lot of people. Death to that kind of human! Go away! They ate humans! Disgusting! They ate humans! I wasn’t aware of anything. Of the murders, yes, but they ate humans! Humans! They smell like human flesh!”

Now, Germany does not have a Queen, nor is Mickey Mouse a real live mortal being (sorry for the spoiler, kids). Were other royals and plutocrats engaged in cannibalism? Unfortunately, the sudden disappearance of Ms Jiménez makes it difficult to work out what she was alleging, let alone the truth of such claims. But conspiracy theories love angry rants and disappearing complainants, and so a (smallish) cult has followed Jiménez, particularly after an anonymous person on a blog called “The Black Manik” claimed to have spoken to Jimenez and witnessed the incident, until he was pulled away by “some tall, well-dressed people”. Accusations fly thick and fast about elites and their alleged members, some of whom are occasionally accused of being rich cannibals.

Despite the best efforts of the Daily Mail, no further sightings of Gabriela Rico Jiménez have been reported.

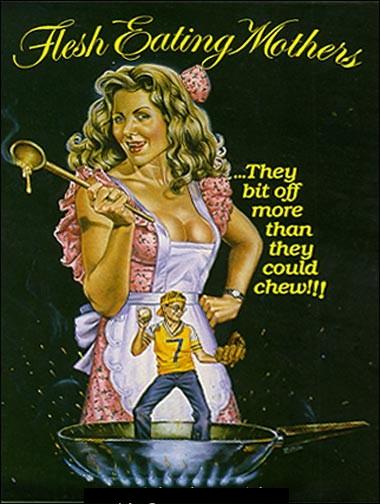

The narrative of cannibalism to describe class warfare is nothing new – in 1789, the sans-culottes felt that French aristocrats were (perhaps metaphorically) eating their flesh, and in turn, the poor eating the aristocrats (more literally) became popular after the Revolution. In films, there are a lot of phantasies about the poor eating the rich, such as the silly English movie Eat the Rich. Indigenous people were routinely accused of eating their European invaders, often as a pretext for enslavement and extermination, but sometimes the eating of the foreigner was presented as a form of liberation. Sawney Bean and his incestuous clan were supposedly preying on rich travellers in the fifteenth century, and have been revived for horror stories ever since. We see cannibalism as a form of revenge on rich exploiters in the classic Suddenly Last Summer, in which the rich, white, effete Sebastian is eaten by the impoverished boys he has been sexually abusing.

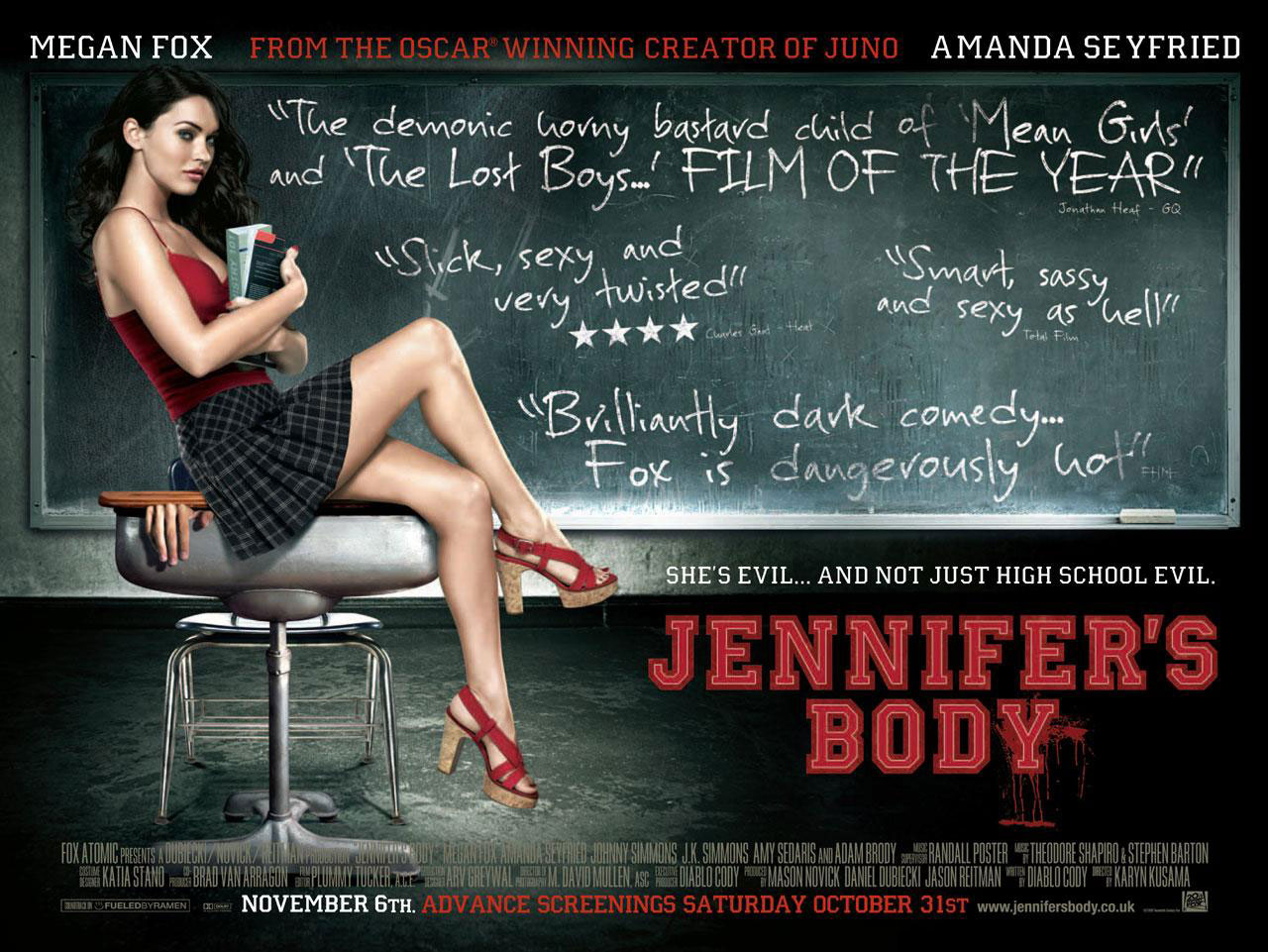

But the more realistic horror movies usually show those with money, influence and power eating the poor. Jack the Ripper was never conclusively identified, but seems to have been someone rich and powerful, who got his kicks in 1888 from killing sex workers and, in one case at least, eating parts of them. The film Never Let Me Go showed a future (or alternate present) in which the protagonists were bred as clones, not to be eaten exactly, but to be cut up for organ transplants. More recently, films have speculated on the rich forming clubs to eat the poor, or paying entrepreneurs to kidnap and sell parts of young women to satiate their jaded appetites. In the wonderful Welsh film The Feast, the rich are over-consumers of the environment, and their punishment is to eat each other. And let’s not forget the extraordinary accusations made against actor Armie Hammer, who declared to a girlfriend on social media “I am 100% a cannibal. I want to eat you.”

So it’s not clear who is eating whom – the rich or the poor, or perhaps there is some sort of cultural pendulum. But leaving aside the actual flesh, we are all involved in consumption of the other in some form. Philosophers from Voltaire to Derrida have declared “we are all cannibals”.